THE VISIT AND ESTABLISHMENT OF MONTAIGUT BY RICHARD THE LIONHEART: ÉGLISE NOTRE-DAME MONTAIGUT

MONTAIGUT EN COMBRAILLE

The visit to Montaigut of Eleanor and Richard the lionheart.

MONTAIGUT TODAY. THE WALLS OF AN ANCIENT CITY. THE BOTTOM ROAD IS LOCATED ABOVE THE FORTIFICATION WALLS. THE CHURCH IS AT THE LEFT MIDDLE EDGE OF THE PHOTO.

Upon the death of her husband Henry II on 6 July 1189, Richard I was the undisputed heir. One of his first acts as king was to send William Marshal to England with orders to release Eleanor from prison; he found upon his arrival that her custodians had already released her. Eleanor rode to Westminster and received the oaths of fealty from many lords and prelates on behalf of the king. She ruled England in Richard's name, signing herself "Eleanor, by the grace of God, Queen of England". On 13 August 1189, Richard sailed from Barfleur to Portsmouth and was received with enthusiasm. Eleanor ruled England as regent while Richard went off on the Third Crusade. Later, when Richard was captured, she personally negotiated his ransom by going to Germany.

Eleanor survived Richard and lived well into the reign of her youngest son, King John. In 1199, under the terms of a truce between King Philip II and King John, it was agreed that Philip's twelve-year-old heir-apparent Louis would be married to one of John's nieces, daughters of his sister Eleanor of Castile. John instructed his mother to travel to Castile to select one of the princesses. Now 77, Eleanor set out from Poitiers. Just outside Poitiers she was ambushed and held captive by Hugh IX of Lusignan, whose lands had been sold to Henry II by his forebears. Eleanor secured her freedom by agreeing to his demands. She continued south, crossed the Pyrenees, and travelled through the Kingdoms of Navarre and Castile, arriving in Castile before the end of January 1200.

King Alfonso VIII and Eleanor's daughter, Queen Eleanor of Castile, had two remaining unmarried daughters, Urraca and Blanche. Eleanor selected the younger daughter, Blanche. She stayed for two months at the Castilian court, then late in March journeyed with granddaughter Blanche back across the Pyrenees. She celebrated Easter in Bordeaux, where the famous warrior Mercadier came to her court. It was decided that he would escort the Queen and Princess north. "On the second day in Easter week, he was slain in the city by a man-at-arms in the service of Brandin", a rival mercenary captain. This tragedy was too much for the elderly queen, who was fatigued and unable to continue to Normandy. She and Blanche rode in easy stages to the valley of the Loire, and she entrusted Blanche to the Archbishop of Bordeaux, who took over as her escort. The exhausted Eleanor went to Fontevraud, where she remained. In early summer, Eleanor was ill and John visited her at Fontevraud.

Eleanor was again unwell in early 1201. When war broke out between John and Philip, Eleanor declared her support for John and set out from Fontevraud to her capital Poitiers to prevent her grandson Arthur I, Duke of Brittany, posthumous son of Eleanor's son Geoffrey and John's rival for the English throne, from taking control. Arthur learned of her whereabouts and besieged her in the castle of Mirabeau. As soon as John heard of this, he marched south, overcame the besiegers, and captured the 15-year-old Arthur. Eleanor then returned to Fontevraud where she took the veil as a nun.

Eleanor died in 1204 and was entombed in Fontevraud Abbey next to her husband Henry and her son Richard. Her tomb effigy shows her reading a bible and is decorated with magnificent jewelry. By the time of her death she had outlived all of her children except for King John of England and Queen Eleanor of Castile.

|

Notre-Dame-de-Bonne-Nouvelle church.

Coat of arms |

Montaigut existed about 1230 when a charter was given to seigneur bourbon l'archambault demontaigne. The church was older still. Although there is not much information of that period, his wooden castle was turned down and burned by another seigneur de Blot.

Far over the misty mountains lies Montaigut

In the south entree of the site you see a proclamation of the visit that was brought by Eleonore d'Aquitaine her son Richard the lionheart, then Count of Poitiers. After Henry II fell seriously ill in 1170, he put in place his plan to divide his kingdom, although he would retain overall authority over his sons and their territories. In 1171 Richard left for Aquitaine with his mother, and Henry II gave him the duchy of Aquitaine at the request of Eleanor.[26] Richard and his mother embarked on a tour of Aquitaine in 1171 in an attempt to pacify the locals.[27] Together they laid the foundation stone of St Augustine's Monastery in Limoges. In June 1172 Richard was formally recognised as the Duke of Aquitaine when he was granted the lance and banner emblems of his office; the ceremony took place in Poitiers and was repeated in Limoges, where he wore the ring of St Valerie, who was the personification of Aquitaine.

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 6 July 1189 until his death. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Count of Nantes, and Overlord of Brittany at various times during the same period. He was known as Cœur de Lion, or Richard the Lionheart, even before his accession, because of his reputation as a great military leader and warrior.[1] The Saracens called him Melek-Ric or Malek al-Inkitar - King of England.[2]

By the age of sixteen Richard was commanding his own army, putting down rebellions in Poitou against his father, King Henry II.[1] Richard was a central Christian commander during the Third Crusade, effectively leading the campaign after the departure of Philip Augustus and scoring considerable victories against his Muslim counterpart, Saladin, but was unable to reconquer Jerusalem.[3]

Although speaking only French and spending very little time in England (he lived in his Duchy of Aquitaine in the southwest of France, preferring to use his kingdom as a source of revenue to support his armies),[4] he was seen as a pious hero by his subjects.[5] He remains one of the very few Kings of England remembered by his epithet, rather than regnal number, and is an enduring, iconic figure in England.

913 : Origin of the lordship of Montaigut

1160 : War between Archambault VI and the lord of Blot

1171 : Queen Eleanore of England Plantagenet and her son Richard the Lion Heart just resolve the conflict (Pacify the Locals)

1210 : Reconstruction of the castle by Guy de Dampierre

1238 : Death of Archambault VIII at the Battle of Cognac (lying at the Abbey of Bellaigues)

1440 : Visit of King Charles VII during the Praguerie (revolt against his reforms).

1633 : The castle was dismantled by order of Richelieu

1793 : Montaigut becomes Township

Beynac

Château-Rocher from the Sioule valley

The "romantic ruins of Château Rocher",[1] standing on a cliff above the river, are the remains of a 13th-century construction, with evidence of earlier (11th century) building. The castle was built by theLords of Bourbon. A masonry bridge crossing the moat comes up against the entry door, now ruined, and the outer wall. A second wall existed in front of the two eastern towers. Three principal towers flanked the east and north fronts.

The story of that amazingly influential and still somewhat mysterious woman, Eleanor of Aquitaine, has the dramatic interest of a novel. She was at the very center of the rich culture and clashing politics of the twelfth century. Richest marriage prize of the Middle Ages, she was Queen of France as the wife of Louis VII, and went with him on the exciting and disastrous Second Crusade. Inspiration of troubadours and trouvères, she played a large part in rendering fashionable the Courts of Love and in establishing the whole courtly tradition of medieval times. Divorced from Louis, she married Henry Plantagenet, who became Henry II of England. Her resources and resourcefulness helped Henry win his throne, she was involved in the conflict over Thomas Becket, and, after Henry’s death, she handled the affairs of the Angevin empire with a sagacity that brought her the trust and confidence of popes and kings and emperors.

Having been first a Capet and then a Plantagenet, Queen Eleanor was the central figure in the bitter rivalry between those houses for the control of their continental domains—a rivalry that excited the whole period: after Henry’s death, her sons, Richard Coeur-de-Lion and John “Lackland” (of Magna Carta fame), fiercely pursued the feud up to and even beyond the end of the century. But the dynastic struggle of the period was accompanied by other stirrings: the intellectual revolt, the struggle between church and state, the secularization of literature and other arts, the rise of the distinctive urban culture of the great cities. Eleanor was concerned with all the movements, closely connected with all the personages; and she knew every city from London and Paris to Byzantium, Jerusalem, and Rome.

Dauphins of Auvergne

Coat of arms of the dauphins of Auvergne.

What is by convenience called the Dauphinate of Auvergne was in reality the remnant of the County of Auvergne after the usurpation of Count William VII the Young around 1155 by his uncle Count William VIII the Old.

The young count was able to maintain his status in part of his county, especiallyBeaumont, Chamaliers, and Montferrand. Some authors have therefore named William VII and his descendants Counts of Clermont, although this risks confusion with theCounty of Clermont in Beauvaisis and the episcopal County of Clermont in Auvergne.

The majority of authors, however, anticipating the formalization of the dauphinate in 1302, choose to call William VII and his successors the Dauphins of Auvergne. Still others, out of convenience, choose to call these successors the Counts-Dauphins of Auvergne.

The title of Dauphin of Auvergne was derived from William VII's mother, who was the daughter of theDauphin de Viennois, Guigues IV. This meant that William VII's male descendants were usually givenDauphin as a surname.

The numbering of the Counts-turned-Dauphins is complicated. Some authors create a new numbering starting with the first dauphins even though the dauphinate did not really begin until 1302. Others choose to reestablish, beginning with William the Young, the numbering of the viscounts of Clermont who became counts of Auvergne, particularly for the dauphins named Robert.

Longitude : 2.8094110 Latitude : 46.1810690

The Combrailles area

"Les Combrailles" is a plateau in the north-east area of the Puy-de-Dôme, with valleys and gorges and dotted with peaceful villages. An area offering a well-preserved natural setting.

With the rivers, streams, waterfalls and pools, water is to be found wherever you look in the Combrailles, offering a paradise for those who enjoy fishing, bathing and water sports.

The Sioule River crosses the Combrailles area, carving out gorges and also the must-see Queille meander. Discover the Sioule by canoe or kayak, departing from the Menat bridge, or go swimmingorfishing in the ponds and lakes of the area.

Combrailles is also a very volcanic area, traversed by the Chaîne des Puys. Discover the area onhorseback or on foot, with a walk around the Gour de Tazenat crater lake, or the Chemin Fais'Artdiscovery trail. To learn even more, visit the two sites dealing with the themes of the region’s volcanic activity Vulcania and the Lemptégy volcano.

The Chateau Dauphin gardens

Cultural and historical heritage

Among the natural beauty of Les Combrailles lies historical sites, including the Manor of Veygoux, the childhood home of General Desaix that today is an interactive museum dedicated to the French Revolution.

The Combrailles is also a land of castles, including the impressive Chateau Rocher overlooking the Sioule River and the 12th century Chateau Dauphin with its impressive gardens. Also discover the churches of the area, Menat Abbey, a cluniac site, the unique capitals of the Saint-Pierrechurch in Biollet, and the painted interiors of the Saint-Légerchurch in Montfermy.

Also of note is the town of Chateauneuf-les-Bains, a pleasant spa resort located in the Sioule gorges, a part of the Massif Central Spa Trail.

The locals are particularly attached to biodiversity and to the protection of the Combrailles area’s natural resources. This flair for skilled work can be clearly seen in the region's craft industries. The local artisans- potters, spinners, enamellers, ironworkers, sculptors and glassmakers possess unique know-how in their respective fields. Local traditions also live on through the village festivals, markets, fairs and concerts organised here throughout the year!

Whether you’re staying in a hotel, a B&B, a gîte or a campsite, you'll be dealing with accommodation providers and restaurant owners with a passion for their work and their region, all too happy to pass on their enthusiasm for the Combrailles area.

Montaigut Yesterday

|

|

Montaigut existed about 1230 when a charter was given to seigneur bourbon l'archambault de montaigne. The church was older still. Although there is not much information of that period, his wooden castle was turned down and burned by another seigneur de Blot.

|

|

|

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor's effigy at Fontevraud Abbey.

Eleanor's succession to the duchy of Aquitaine in 1137 made her the most eligible bride in Europe. Three months after she became duchess, she married King Louis VII of France, son of her guardian, King Louis VI. As Queen of France, she participated in the unsuccessful Second Crusade. Soon after, Eleanor sought an annulment of her marriage,[1] but her request was rejected by Pope Eugene III.[2] However, after the birth of her second daughter Alix, Louis agreed to an annulment in consideration of her failure to bear a son after fifteen years of marriage.[3] The marriage was annulled on 11 March 1152 on the grounds of consanguinity within the fourth degree. Their daughters were declared legitimate and custody was awarded to Louis, while Eleanor's lands were restored to her.

As soon as the annulment was granted, Eleanor became engaged to Henry, Duke of Normandy, who became King Henry II of England in 1154. Henry was her third cousin (cousin of the third degree), and nine years younger. The couple married on 18 May 1152 (Whit Sunday), eight weeks after the annulment of Eleanor's first marriage, in a cathedral in Poitiers, France. Over the next thirteen years, she bore Henry eight children: five sons, three of whom would become kings; and three daughters. However, Henry and Eleanor eventually became estranged. Henry imprisoned her in 1173 for supporting her sonHenry's revolt against her husband, and she was not released until 1189 when Henry died (on 6 July), and their son ascended the English throne as Richard I.

Eleanor's year of birth is not known precisely: a late 13th-century genealogy of her family listing her as 13 years old in the spring of 1137 provides the best evidence that Eleanor was perhaps born as late as 1124.[4] On the other hand, some chronicles mention a fidelity oath of some lords of Aquitaine on the occasion of Eleanor's fourteenth birthday in 1136. This, and her known age of 82 at her death, make 1122 more likely the year of birth.[5] Her parents almost certainly married in 1121. Her birthplace may have beenPoitiers, Bordeaux, or Nieul-sur-l'Autise, where her mother and brother died when Eleanor was 6 or 8.[6]

Eleanor is said to have been named for her mother Aenor and called Aliénor from the Latin alia Aenor, which means the other Aenor. It became Eléanor in the langues d'oïl of Northern France and Eleanor in English.[3] There was, however, another prominent Eleanor before her: Eleanor of Normandy, an aunt ofWilliam the Conqueror, who lived a century earlier than Eleanor of Aquitaine. In Paris as the Queen of France she was called Helienordis, her honorific name as written in the Latin epistles.

By all accounts, Eleanor's father ensured that she had the best possible education. Eleanor came to learn arithmetic, the constellations, and history.[3] She did learn domestic skills such as household management and the needle arts of embroidery, needlepoint, sewing, spinning, and weaving.[3] Eleanor ended up developing skills in conversation, dancing, games such as backgammon, checkers, and chess, playing the harp, and singing.[3] Although her native tongue was Poitevin, she was taught to read and speak Latin, was well versed in music and literature, and schooled in riding, hawking, and hunting.[8]Eleanor was extroverted, lively, intelligent, and strong-willed. In the spring of 1130, her four-year-old brother William Aigret and their mother died at the castle of Talmont, on Aquitaine's Atlantic coast. Eleanor became the heir presumptive to her father's domains. The Duchy of Aquitaine was the largest and richest province of France; Poitou (where Eleanor spent most of her childhood) and Aquitaine together were almost one-third the size of modern France. Eleanor had only one other legitimate sibling, a younger sister named Aelith, also called Petronilla. Her half brother Joscelin was acknowledged by William X as a son, but not as his heir. That she had another half brother, William, has been discredited.[9] Later, during the first four years of Henry II's reign, her siblings joined Eleanor's royal household.

Inheritance

Eleanor, aged twelve to fifteen, then became the Duchess of Aquitaine, and thus the most eligible heiress in Europe. As these were the days when kidnapping an heiress was seen as a viable option for obtaining a title, William dictated a will on the very day he died that bequeathed his domains to Eleanor and appointed King Louis VI of France as her guardian.[10] William requested the king to take care of both the lands and the duchess, and to also find her a suitable husband. However, until a husband was found, the king had the legal right to Eleanor's lands. The duke also insisted to his companions that his death be kept a secret until Louis was informed – the men were to journey from Saint James of Compostela across the Pyrenees as quickly as possible to call at Bordeaux to notify the archbishop, then to make all speed to Paris to inform the king.

The king of France, known as Louis the Fat, was also gravely ill at that time, suffering from a bout ofdysentery from which he appeared unlikely to recover. Despite his impending mortality, Louis remained clear-minded. His heir, Prince Louis, had originally been destined for the monastic life of a younger son but became Dauphin when his older brother, Philip, died from a riding accident.[11] The death of William, one of the king's most powerful vassals, made available the most desirable duchy in France. While presenting a solemn and dignified face to the grieving Aquitainian messengers, Louis exulted when they departed. Rather than act as guardian to the duchess and duchy, he decided to marry the duchess to his 17-year-old heir and bring Aquitaine under the control of the French crown, thereby greatly increasing the power and prominence of France and its ruling family, the Capets. Within hours the king had arranged for Prince Louis to be married to Eleanor, with Abbot Suger in charge of the wedding arrangements. Prince Louis was sent to Bordeaux with an escort of 500 knights, along with Abbot Suger, Theobald II, Count of Champagne, and Count Ralph.

First marriage

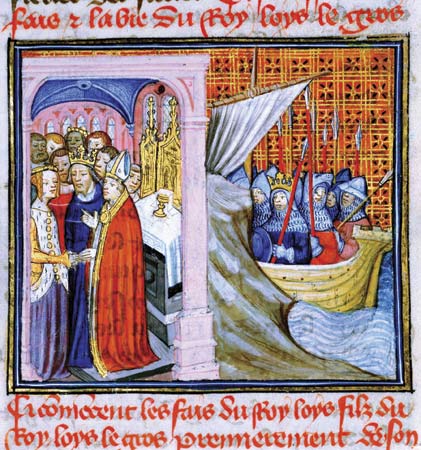

At left, a 14th-century representation of the wedding of Louis and Eleanor; at right, Louis leaving on Crusade.

|  |

Eleanor's grandfather, William IX of Aquitaine, gave her this rock crystal vase, which she gave to Louis as a wedding gift. He later donated it to theAbbey of Saint-Denis. This is the only surviving artifact known to have belonged to Eleanor.

On 25 July 1137 Louis and Eleanor were married in the Cathedral of Saint-André in Bordeaux by the Archbishop of Bordeaux.[7]Immediately after the wedding, the couple was enthroned as Duke and Duchess of Aquitaine. However, there was a catch: the land would remain independent of France until Eleanor's oldest son became both King of the Franks and Duke of Aquitaine. Thus, her holdings would not be merged with France until the next generation. As a wedding present she gave Louis a rock crystal vase currently on display at the Louvre. Louis gave the vase to the Saint Denis Basilica. This vase is the only object connected with Eleanor of Aquitaine that still survives.[13]

Louis's tenure as Count of Poitou and Duke of Aquitaine and Gascony lasted only few days. Although he had been invested as such on 8 August 1137, a messenger gave him the news that Louis VI had died of dysentery on 1 August while Prince Louis and Eleanor were making a tour of the provinces. Thus he became King Louis VII of France. He and Eleanor were anointed and crowned King and Queen of the Franks on Christmas Day of the same year.[7][14]

Possessing a high-spirited nature, Eleanor was not popular with the staid northerners; according to sources, Louis's mother Adélaide de Maurienne thought her flighty and a bad influence. She was not aided by memories of Constance of Arles, the Provençal wife of Robert II, tales of whose immodest dress and language were still told with horror.[ Eleanor's conduct was repeatedly criticized by church elders, particularly Bernard of Clairvaux and Abbot Suger, as indecorous. The king was madly in love with his beautiful and worldly bride, however, and granted her every whim, even though her behavior baffled and vexed him. Much money went into making the austere Cité Palace in Paris more comfortable for Eleanor's sake.[11]

Conflict[edit]

Although Louis was a pious man, he soon came into a violent conflict with Pope Innocent II. In 1141, theArchbishopric of Bourges became vacant, and the king put forward as a candidate one of his chancellors, Cadurc, while vetoing the one suitable candidate, Pierre de la Chatre, who was promptly elected by the canons of Bourges and consecrated by the pope. Louis accordingly bolted the gates of Bourges against the new bishop. The pope, recalling similar attempts by William X to exile supporters of Innocent from Poitou and replace them with priests loyal to himself, blamed Eleanor, saying that Louis was only a child and should be taught manners. Outraged, Louis swore upon relics that so long as he lived Pierre should never enter Bourges. An interdict was thereupon imposed upon the king's lands, and Pierre was given refuge by Theobald II, Count of Champagne.

Louis became involved in a war with Count Theobald by permitting Raoul I, Count of Vermandois andseneschal of France, to repudiate his wife Eléonore of Blois, Theobald's sister, and to marry Petronilla of Aquitaine, Eleanor's sister. Eleanor urged Louis to support her sister's marriage to Count Raoul. Theobald had also offended Louis by siding with the pope in the dispute over Bourges. The war lasted two years (1142–44) and ended with the occupation of Champagne by the royal army. Louis was personally involved in the assault and burning of the town of Vitry. More than a thousand people who sought refuge in the church there died in the flames. Horrified, and desiring an end to the war, Louis attempted to make peace with Theobald in exchange for his support in lifting the interdict on Raoul and Petronilla. This was duly lifted for long enough to allow Theobald's lands to be restored; it was then lowered once more when Raoul refused to repudiate Petronilla, prompting Louis to return to Champagne and ravage it once more.

In June 1144, the king and queen visited the newly built monastic church at Saint-Denis. While there, the queen met with Bernard of Clairvaux, demanding that he have the excommunication of Petronilla and Raoul lifted through his influence on the pope, in exchange for which King Louis would make concessions in Champagne and recognise Pierre de la Chatre as Archbishop of Bourges. Dismayed at her attitude, Bernard scolded Eleanor for her lack of penitence and interference in matters of state. In response, Eleanor broke down and meekly excused her behaviour, claiming to be bitter because of her lack of children. In response, Bernard became more kindly towards her: "My child, seek those things which make for peace. Cease to stir up the King against the Church, and urge upon him a better course of action. If you will promise to do this, I in return promise to entreat the merciful Lord to grant you offspring." In a matter of weeks, peace had returned to France: Theobald's provinces were returned and Pierre de la Chatre was installed as Archbishop of Bourges. In April 1145, Eleanor gave birth to a daughter, Marie.

Louis, however, still burned with guilt over the massacre at Vitry and wished to make a pilgrimage to theHoly Land to atone for his sins. Fortunately for him, in the autumn of 1145, Pope Eugene III requested that Louis lead a Crusade to the Middle East to rescue the Frankish Kingdoms there from disaster. Accordingly, Louis declared on Christmas Day 1145 at Bourges his intention of going on crusade.

Crusade[edit]

Eleanor of Aquitaine also formally took up the cross symbolic of the Second Crusade during a sermon preached by Bernard of Clairvaux. In addition, she had been corresponding with her uncle Raymond, Prince of the Crusader kingdom of Antioch, who was seeking further protection against the "Saracens" from the French crown. Eleanor recruited some of her royal ladies-in-waiting for the campaign, as well as 300 non-noble Aquitainian vassals. She insisted on taking part in the Crusades as the feudal leader of the soldiers from her duchy. The story that she and her ladies dressed as Amazons is disputed by historians, sometimes confused with the account of King Conrad's train of ladies during this campaign (in Edward Gibbon's The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire). Her testimonial launch of the Second Crusade from Vézelay, the rumored location of Mary Magdalene´s grave, dramatically emphasized the role of women in the campaign.

The Crusade itself achieved little. Louis was a weak and ineffectual military leader with no skill for maintaining troop discipline or morale, or of making informed and logical tactical decisions. In eastern Europe, the French army was at times hindered by Manuel I Comnenus, the Byzantine Emperor, who feared that the Crusade would jeopardize the tenuous safety of his empire. Notwithstanding, during their three-week stay at Constantinople, Louis was fêted and Eleanor was much admired. She was compared with Penthesilea, mythical queen of the Amazons, by the Greek historian Nicetas Choniates. He added that she gained the epithet chrysopous (golden-foot) from the cloth of gold that decorated and fringed her robe. Louis and Eleanor stayed in the Philopation palace just outside the city walls.

| |

From the moment the Crusaders entered Asia Minor, things began to go badly. The king and queen were still optimistic – the Byzantine Emperor had told them that the German King Conrad had won a great victory against a Turkish army (when in fact the German army had been massacred), and the troupe was still eating well. However, while camping near Nicea, the remnants of the German army, including a dazed and sick King Conrad, staggered past the French camp, bringing news of their disaster. The French, with what remained of the Germans, then began to march in increasingly disorganized fashion towards Antioch. They were in high spirits on Christmas Eve, when they chose to camp in a lush Dercervian valley near Ephesus. Here they were ambushed by a Turkish detachment; the French proceeded to slaughter this detachment and appropriate their camp.

Louis then decided to cross the Phrygian mountains directly in the hope of reaching Eleanor's uncle Raymond in Antioch more quickly. As they ascended the mountains, however, the army and the king and queen were horrified to discover the unburied corpses of the previously slaughtered German army.

On the day set for the crossing of Mount Cadmos, Louis chose to take charge of the rear of the column, where the unarmed pilgrims and the baggage trains marched. The vanguard, with which Queen Eleanor marched, was commanded by her Aquitainian vassal Geoffrey de Rancon. Unencumbered by baggage, they reached the summit of Cadmos, where Rancon had been ordered to make camp for the night. Rancon however chose to continue on, deciding in concert with Amadeus III, Count of Savoy (Louis's uncle) that a nearby plateau would make a better campsite: such disobedience was reportedly common.

Accordingly, by mid-afternoon, the rear of the column – believing the day's march to be nearly at an end – was dawdling. This resulted in the army becoming separated, with some having already crossed the summit and others still approaching it. At this point the Turks, who had been following and feinting for many days, seized their opportunity and attacked those who had not yet crossed the summit. The French (both soldiers and pilgrims), taken by surprise, were trapped; those who tried to escape were caught and killed. Many men, horses, and much of the baggage were cast into the canyon below. The chroniclerWilliam of Tyre, writing between 1170 and 1184 and thus perhaps too late to be considered historically accurate, placed the blame for this disaster firmly on the amount of baggage (much of it reputedly belonging to Eleanor and her ladies) and the presence of non-combatants.

The king, having scorned royal apparel in favour of a simple pilgrim's tunic, escaped notice (unlike his bodyguards, whose skulls were brutally smashed and limbs severed). He reportedly "nimbly and bravely scaled a rock by making use of some tree roots which God had provided for his safety", and managed to survive the attack. Others were not so fortunate: "No aid came from Heaven, except that night fell."[16]

Official blame for the disaster was placed on Geoffrey de Rancon, who had made the decision to continue, and it was suggested that he be hanged (a suggestion which the king ignored). Since he was Eleanor's vassal, many believed that it was she who had been ultimately responsible for the change in plan, and thus the massacre. This did nothing for her popularity in Christendom – she was also blamed for the size of the baggage train and the fact that her Aquitainian soldiers had marched at the front, thus not involved in the fight. Continuing on, the army became split, with the commoners marching toward Antioch and the royalty traveling by sea. When most of the land army arrived, the king and queen had a profound dispute. Some, such as John of Salisbury and William of Tyre, say Eleanor's reputation was sullied by rumours of an affair with her uncle Raymond. However, this may have been a ruse, as Raymond through Eleanor tried to sway Louis forcibly to use his army to attack the actual Muslim encampment at nearby Aleppo, gateway to retaking Edessa, by papal decree the objective of the Crusade. Although this was perhaps the better military plan, Louis was not keen to fight in northern Syria. One of Louis's avowed Crusade goals was to journey in pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and he stated his intention to continue. Reputedly Eleanor then requested to stay with Raymond and brought up the matter of consanguinity – the fact that she and her husband, King Louis, were too closely related. This was grounds for divorce in the medieval period. Rather than allowing her to stay, Louis took Eleanor from Antioch against her will and continued on to Jerusalem with his dwindling army .[17]

This episode humiliated Eleanor, and she maintained a low profile for the rest of the crusade. Louis's subsequent assault on Damascus in 1148 with his remaining army, fortified by King Conrad and Baldwin III of Jerusalem, achieved little. Damascus was a major trading centre that abounded in wealth and was under normal circumstances a potential threat, but the rulers of Jerusalem had recently entered into a truce with the city, which they then forswore. It was a gamble that did not pay off, and whether through military error or betrayal, the Damascus campaign was a failure. The French royal family retreated to Jerusalem and then sailed to Rome and made their way back to Paris.

While in the eastern Mediterranean, Eleanor learned about maritime conventions developing there, which were the beginnings of what would become admiralty law. She introduced those conventions in her own lands on the island of Oleron in 1160 (with the "Rolls of Oléron") and later in England as well. She was also instrumental in developing trade agreements with Constantinople and ports of trade in the Holy Lands.

Annulment[edit]

Even before the Crusade, Eleanor and Louis were becoming estranged, and their differences were only exacerbated while they were abroad. Eleanor's purported relationship with her uncle Raymond,[18] the ruler of Antioch, was a major source of discord. Eleanor supported her uncle's desire to re-capture the nearby County of Edessa, the objective of the Crusade. In addition, having been close to him in their youth, she now showed what was considered to be "excessive affection" toward her uncle. Raymond had plans to abduct Eleanor, to which she consented.[19] While many historians today dismiss this as normal affection between uncle and niece (noting their early friendship and his similarity to her father and grandfather), many of Eleanor's adversaries interpreted the generous displays of affection as an incestuous affair. Louis's long march to Jerusalem and back north, which Eleanor was forced to join, debilitated his army and disheartened her knights; the divided Crusade armies could not overcome the Muslim forces, and the royal couple had to return home.

Home, however, was not easily reached. Louis and Eleanor, on separate ships due to their disagreements, were first attacked in May 1149 by Byzantine ships attempting to capture both on the orders of the Byzantine Emperor. Although they escaped this attempt unharmed, stormy weather drove Eleanor's ship far to the south (to the Barbary Coast) and caused her to lose track of her husband. Neither was heard of for over two months. In mid-July, Eleanor's ship finally reached Palermo in Sicily, where she discovered that she and her husband had both been given up for dead. She was given shelter and food by servants of King Roger II of Sicily, until the king eventually reached Calabria, and she set out to meet him there. Later, at King Roger's court in Potenza, she learned of the death of her uncle Raymond, who was beheaded by Muslim forces in the Holy Land. This appears to have forced a change of plans, for instead of returning to France from Marseilles, they went to see Pope Eugene III in Tusculum, where he had been driven five months before by a revolt of the Commune of Rome.

Eugene did not, as Eleanor had hoped, grant an annulment. Instead, he attempted to reconcile Eleanor and Louis, confirming the legality of their marriage. He proclaimed that no word could be spoken against it, and that it might not be dissolved under any pretext. Eventually, he arranged events so that Eleanor had no choice but to sleep with Louis in a bed specially prepared by the pope. Thus was conceived their second child – not a son, but another daughter, Alix of France.

The marriage was now doomed. Still without a son and in danger of being left with no male heir, facing substantial opposition to Eleanor from many of his barons and her own desire for divorce, Louis bowed to the inevitable. On 11 March 1152, they met at the royal castle of Beaugency to dissolve the marriage. Hugues de Toucy, Archbishop of Sens, presided, and Louis and Eleanor were both present, as were the Archbishops of Bordeaux and Rouen. Archbishop Samson of Reims acted for Eleanor.

On 21 March, the four archbishops, with the approval of Pope Eugene, granted an annulment on grounds of consanguinity within the fourth degree (Eleanor was Louis' third cousin once removed, and shared common ancestry with Robert II of France). Their two daughters were, however, declared legitimate and custody of them was awarded to King Louis. Archbishop Samson received assurances from Louis that Eleanor's lands would be restored to her.

Second marriage

Henry II of England

|  |

The marriage of Eleanor of Aquitaine to Henry of Anjou and Henry's subsequent succession to the throne of England created the Angevin empire.

As Eleanor traveled to Poitiers, two lords – Theobald V, Count of Blois, and Geoffrey, Count of Nantes(brother of Henry II, Duke of Normandy) – tried to kidnap and marry her to claim her lands. As soon as she arrived in Poitiers, Eleanor sent envoys to Henry, Duke of Normandy and future king of England, asking him to come at once to marry her. On 18 May 1152 (Whit Sunday), eight weeks after her annulment, Eleanor married Henry "without the pomp and ceremony that befitted their rank".[20]

Eleanor was related to Henry even more closely than she had been to Louis – they were cousins to the third degree through their common ancestor, Ermengarde of Anjou (wife of Robert I, Duke of Burgundyand Geoffrey, Count of Gâtinais), and they were also descended from King Robert II of France. A marriage between Henry, and Eleanor's daughter Marie, had earlier been declared impossible due to their status as third cousins once removed. It was rumored by some that Eleanor had had an affair with Henry's own father, Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, who had advised his son to avoid any involvement with her.

On 25 October 1154, Henry became King of England. Eleanor was crowned Queen of England by theArchbishop of Canterbury on 19 December 1154.[14] She may not have been anointed on this occasion, however, because she had already been anointed in 1137.[21]Over the next thirteen years, she bore Henry five sons and three daughters: William, Henry, Richard, Geoffrey, John, Matilda, Eleanor, and Joan. John Speed, in his 1611 work History of Great Britain, mentions the possibility that Eleanor had a son named Philip, who died young. His sources no longer exist, and he alone mentions this birth.[22]

Eleanor's marriage to Henry was reputed to be tumultuous and argumentative, although sufficiently cooperative to produce at least eight pregnancies. Henry was by no means faithful to his wife and had a reputation for philandering. Henry fathered other, illegitimate children throughout the marriage. Eleanor appears to have taken an ambivalent attitude towards these affairs: for example, Geoffrey of York, an illegitimate son of Henry, was acknowledged by Henry as his child and raised at Westminster in the care of the queen.

During the period from Henry's accession to the birth of Eleanor's youngest son John, affairs in the kingdom were turbulent: Aquitaine, as was the norm, defied the authority of Henry as Eleanor's husband and answered only to their Duchess. Attempts were made to claimToulouse, the rightful inheritance of Eleanor's grandmother Philippa of Toulouse, but they ended in failure. A bitter feud arose between the king and Thomas Becket, initially his Chancellor and closest adviser and later the Archbishop of Canterbury. Louis of France had remarried and been widowed; he married for the third time and finally fathered a long hoped-for son, Philip Augustus (also known as Dieudonne - God-given). "Young Henry," son of Henry and Eleanor, wed Margaret of France, daughter of Louis from his second marriage. Little is known of Eleanor's involvement in these events. It is certain that by late 1166, Henry's notorious affair with Rosamund Clifford had become known, and Eleanor's marriage to Henry appears to have become terminally strained.

In 1167, Eleanor's third daughter, Matilda, married Henry the Lion of Saxony. Eleanor remained in England with her daughter for the year prior to Matilda's departure for Normandy in September. Afterwards, Eleanor gathered her movable possessions in England and transported them on several ships to Argentan in December. At the royal court celebrated there that Christmas, she appears to have agreed to a separation from Henry. Certainly, she left for her own city of Poitiers immediately after Christmas. Henry did not stop her; on the contrary, he and his army personally escorted her there before attacking a castle belonging to the rebellious Lusignan family. Henry then went about his own business outside Aquitaine, leaving Earl Patrick (his regional military commander) as her protective custodian. When Patrick was killed in a skirmish, Eleanor (who proceeded to ransom his captured nephew, the young William Marshal), was left in control of her lands.

The Court of Love in Poitiers

Palace of Poitiers, seat of the Counts of Poitou and Dukes of Aquitaine in the 10th through 12th centuries, where Eleanor's highly literate and artistic court inspired tales of Courts of Love.

Of all her influence on culture, Eleanor's time in Poitiers between 1168 and 1173 was perhaps the most critical, yet very little is known about it. Henry II was elsewhere, attending to his own affairs after escorting Eleanor there.[23] Some believe that Eleanor’s court in Poitiers was the "Court of Love", where Eleanor and her daughter Marie meshed and encouraged the ideas of troubadours, chivalry, and courtly love into a single court. It may have been largely to teach manners, as the French courts would be known for in later generations. The existence and reasons for this court are debated.

In The Art of Courtly Love, Andreas Capellanus (Andrew the chaplain) refers to the court of Poitiers. He claims that Eleanor, her daughter Marie, Ermengarde, Viscountess of Narbonne, and Isabelle of Flanders would sit and listen to the quarrels of lovers and act as a jury to the questions of the court that revolved around acts of romantic love. He records some twenty-one cases, the most famous of them being a problem posed to the women about whether true love can exist in marriage. According to Capellanus, the women decided that it was not at all likely.[24]

Some scholars believe that the "court of love" probably never existed, since the only evidence for it is Andreas Capellanus’ book. To strengthen their argument, they state that there is no other evidence that Marie ever stayed with her mother in Poitiers.[23] Andreas wrote for the court of the king of France, where Eleanor was not held in esteem. Polly Schoyer Brooks (the author of a non-academic biography of Eleanor) suggests that the court did exist, but that it was not taken very seriously, and that acts of courtly love were just a “parlor game” made up by Eleanor and Marie in order to place some order over the young courtiers living there.[25]

There is no claim that Eleanor invented courtly love, since it was a concept that had begun to grow before Eleanor’s court arose. All that can be said is that her court at Poitiers was most likely a catalyst for the increased popularity of courtly love literature in the Western European regions.[26] Amy Kelly, in her article, “Eleanor of Aquitaine and her Courts of Love”, gives a very plausible description of the origins of the rules of Eleanor's court: “in the Poitevin code, man is the property, the very thing of woman; whereas a precisely contrary state of things existed in the adjacent realms of the two kings from whom the reigning duchess of Aquitaine was estranged.”[27]

Revolt and capture[edit]

In March 1173, aggrieved at his lack of power and egged on by his father's enemies, the younger Henry launched the Revolt of 1173–1174. He fled to Paris. From there, "the younger Henry, devising evil against his father from every side by the advice of the French King, went secretly into Aquitaine where his two youthful brothers, Richard and Geoffrey, were living with their mother, and with her connivance, so it is said, he incited them to join him". One source claimed that the Queen sent her younger sons to France "to join with him against their father the king". Once her sons had left for Paris, Eleanor may have encouraged the lords of the south to rise up and support them.[30]

Sometime between the end of March and the beginning of May, Eleanor left Poitiers, but was arrested and sent to the king at Rouen. The king did not announce the arrest publicly; for the next year, the Queen's whereabouts were unknown. On 8 July 1174, Henry and Eleanor took ship for England fromBarfleur. As soon as they disembarked at Southampton, Eleanor was taken either to Winchester Castleor Sarum Castle and held there.

Years of imprisonment 1173–1189

The obverse of Eleanor's seal. She is identified as Eleanor, by the Grace of God, Queen of the English, Duchess of the Normans. The legend on the reverse calls her Eleanor, Duchess of the Aquitanians and Countess of the Angevins.[14]

Eleanor was imprisoned for the next sixteen years, much of the time in various locations in England. During her imprisonment, Eleanor became more and more distant with her sons, especially Richard (who had always been her favorite). She did not have the opportunity to see her sons very often during her imprisonment, though she was released for special occasions such as Christmas. About four miles from Shrewsbury and close by Haughmond Abbey is "Queen Eleanor's Bower", the remains of a triangular castle which is believed to have been one of her prisons.

Henry lost the woman reputed to be his great love, Rosamund Clifford, in 1176. He had met her in 1166 and began his liaison in 1173, supposedly contemplating divorce from Eleanor. This notorious affair caused a monkish scribe to transcribe Rosamond's name in Latin to "Rosa Immundi", or "Rose of Unchastity". The king had many mistresses, but although he treated earlier liaisons discreetly, he flaunted Rosamond. He may have done so to provoke Eleanor into seeking an annulment but, if so, the queen disappointed him. Nevertheless, rumours persisted, perhaps assisted by Henry's camp, that Eleanor had poisoned Rosamund. It is also speculated that Eleanor placed Rosamund in a bathtub and had an old woman cut Rosamund's arms.[19] Henry donated much money to Godstow Nunnery, where Rosamund was buried.

In 1183, the Young King Henry tried again to force his father to hand over some of his patrimony. In debt and refused control of Normandy, he tried to ambush his father at Limoges. He was joined by troops sent by his brother Geoffrey and Philip II of France. Henry II's troops besieged the town, forcing his son to flee. After wandering aimlessly through Aquitaine, Henry the Younger caught dysentery. On Saturday, 11 June 1183, the Young King realized he was dying and was overcome with remorse for his sins. When his father's ring was sent to him, he begged that his father would show mercy to his mother, and that all his companions would plead with Henry to set her free. Henry II sent Thomas of Earley,Archdeacon of Wells, to break the news to Eleanor at Sarum. Eleanor reputedly had had a dream in which she foresaw her son Henry's death. In 1193 she would tell Pope Celestine III that she was tortured by his memory.

King Philip II of France claimed that certain properties in Normandy belonged to his half-sister Marguerite, widow of the young Henry, but Henry insisted that they had once belonged to Eleanor and would revert to her upon her son's death. For this reason Henry summoned Eleanor to Normandy in the late summer of 1183. She stayed in Normandy for six months. This was the beginning of a period of greater freedom for the still-supervised Eleanor. Eleanor went back to England probably early in 1184.[30] Over the next few years Eleanor often travelled with her husband and was sometimes associated with him in the government of the realm, but still had a custodian so that she was not free.

Archambault VIII Place

Place was named in reference to Archambault VIII - Lord of Montaigut. He was married to Beatrix Montlucon. They were buried in the abbey of Bellaigue in 1238.

The Belfry is an imposing square tower 30 meters high which houses the town clock.It was built in the thirteenth century as a lookout post. On its bell - Charlotte - 800kg, we read an inscription in Gothic "DABO CIVI CERTAM Horam BUS AND VIATORIBUS": "I will give the exact time for citizens and travelers."

Tower Gate Montmarault, renovated in 2004, is a relic of the time when Montaigut was a walled city.

|

|

|

|

The Belfry

|  |

|

However, this has been challenged. These underground rooms (accessed by a door in the ceiling) were built without latrines, and since the gatehouses at Alnwick and Cockermouth provided accommodation it is unlikely that the rooms would have been used to hold prisoners. An alternative explanation was proposed, suggesting that these were strong-rooms where valuables were stored.

However, this has been challenged. These underground rooms (accessed by a door in the ceiling) were built without latrines, and since the gatehouses at Alnwick and Cockermouth provided accommodation it is unlikely that the rooms would have been used to hold prisoners. An alternative explanation was proposed, suggesting that these were strong-rooms where valuables were stored.

Dungeons, in the plural, have come to be associated with underground complexes of cells and torture chambers. As a result, the number of true dungeons in castles is often exaggerated to interest tourists. Many chambers described as dungeons or oubliettes were in fact storerooms, water-cisterns or even latrines.

Dungeons, in the plural, have come to be associated with underground complexes of cells and torture chambers. As a result, the number of true dungeons in castles is often exaggerated to interest tourists. Many chambers described as dungeons or oubliettes were in fact storerooms, water-cisterns or even latrines.

A wooden skull, placed to spook tourists in Prague Castle. Credit: Adam Jones CC-BY-SA-2.0

A wooden skull, placed to spook tourists in Prague Castle. Credit: Adam Jones CC-BY-SA-2.0 The dungeons of Dunajec Castle, in Poland. Credit: DaLee CC-BY-2.0

The dungeons of Dunajec Castle, in Poland. Credit: DaLee CC-BY-2.0