|  Fireworks and cannon salutes as Russia celebrates 74th anniversary of the Siege of Leningrad during which Nazi troops blockaded St Petersburg for four years and an estimated 800,000 people died

Fireworks exploded above the St Petersburg skyline today, reflecting in the swiftly flowing Neva River as the city celebrated the 74th anniversary of the battle that ended the Siege of Leningrad.

Named at the time after the communist revolutionary, the city was blockaded by German Nazi and Finnish troops for four desperate years during WW2.

By the time the siege ended on January 27, 1944, 872 days later, an estimated 630,000 people had died.

St Petersburg celebrated the 74th anniversary of the battle that ended the four-year-long Siege of Leningrad

Some historians say this is a conservative number, and suggest the real death toll to be closer to 800,000.

The siege began on September 8, 1941, when Nazi forces fully encircled the city, three months after launching Operation Barbarossa against the Soviet Union.

Like the Holocaust, the truth of what occurred took time to trickle outwards, across Europe to France and Britain.

Few people realised the real horror of the siege. For years afterwards Stalin kept it dark.

World War II guns fired a salute during the celebrations which took place today across the city

Fireworks exploded above the austere St Petersburg skyline, reflecting in the swiftly flowing Neva River

A new 3D panorama museum opened in Kirovsk, about 20 miles east of St Petersburg, to mark the occasion

After the Khrushchev thaw, a new legend was propagated. The citizens of Leningrad were heroic in their staunch resistance against hunger and German bombs.

They were willing - and quiet - martyrs for the Revolutionary cause.

But with the collapse of communism, archives opened, as did police records and siege diaries.

The city of almost 3 million, including about 400,000 children, had endured increasingly bleak hardship.

Known at the time as Leningrad, the city was blockaded by German Nazi and Finnish troops for nearly four years during WW2

German and Finnish forces encircled the city, blocking food, ammunition and medical supplies from reaching civilians

Historians suggest the real death toll of the assault to be as high as 800,000 - one in three of the city's population

During the first months of 1942 about 100,000 people were dying every four weeks

It is estimated that more than half of the city's population died during the siege's first year - an extremely cold winter stretching from 1941 to 1942.

Rations fell to just 125 grams of bread per person of which 50 to 60 per cent consisted of sawdust and other inedible bulking agents.

All municipal heating was switched off and the city's people were forced to endure temperatures of as low as -30 degrees celsius.

The death toll peaked in the first two months of 1942 at 100,000 every four weeks.

People died on the streets, and citizens soon became accustomed to the sight of bodies lying sprawled across the pavement.

Nazi shelling was continuous but civilians also had to contend with hunger and temperatures as low as -30 degrees Celsius

USSR officers from the Red Army defended the city using what limited ammunition had been stored there before the war

Rations fell to just 125 grams of bread per person per day, and heating in all municipal buildings was switched off

People became accustomed to the sight of dead bodies in the streets

People were forced to eat pets, dirt and glue.

Some, driven to utter desperation, even resorted to cannibalism. For those willing to break one of humanity's greatest taboos, the streets held an abundance of food.

But as families starved and froze to death inside the city, the German troops outside fared little better.

They had stretched themselves thin and, unlike the Russians, were not used to the bitter cold.

On January 12 of 1944 determined Russian forces broke through the German ranks encircling the city, ending the siege.

|

Operation Barbarossa remains the largest military operation, in terms of manpower, area traversed, and casualties, in human history. The failure of Operation Barbarossa resulted in the eventual defeat of Nazi Germany and is considered a turning point for the Third Reich. Most importantly, Operation Barbarossa opened up the Eastern Front, which ultimately became the biggest theater of war in world history. Operation Barbarossa and the areas which fell under it became the site of some of the largest and most brutal battles, deadliest atrocities, terrible loss of life, and horrific conditions for Soviets and Germans alike - all of which influenced the course of both World War II and the 20th century history.

|

|

The Greatest Battle of All Time – Stalingrad

Mamayev Kurgan is a war memorial like no other on earth ~ for it is dominated by an angry goddess. The most gigantic, impressive and eerie statue in the world, Rodina-Mat, the Mother Goddess of Russia, touts up 160 feet without any pedestal, 20 feet higher than the Statue of Liberty ~ it is the resting place for 35,000 Soviet soldiers who died defending their city, their country and eventually the world.

Feb. 2 marked a very obscure date for Americans, but one that saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of young American boys in World War II ~ it is the 70th anniversary of the final surrender of German forces at Stalingrad ~ The decisive battle of World War II for quite suddenly a glimmer of world wide hope replaced the growing despair of watching an apparently invincible German Wehrmacht, that had conquered the entire European continent in less than three years, brought to its knees by the courageous Russian defenders of Stalingrad.

Americans have never had to defend their country from a fierce fighting force intent on occupying them such as Russia endured in World War 2 ~ so to truly understand the depth of Russian patriotism, as well as other occupied countries and states, we must understand the battle and triumph of Stalingrad against insurmountable odds.

The human cost was truly horrific, as Martin Sieff explains in his commemorative article entitled ~ The Greatest Battle of All Time ~ and Why It Still Matters Today.

Excerpt: “The colossal scale of the fighting between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in what Russians call the Great Patriotic War was well recognized by Americans and Britons at the time but it has been virtually forgotten since. But it dwarfed every other battlefront of the war combined. Eight out of 10 German soldiers killed in World War II died fighting the Red Army. The colossal total of nearly 27 million Soviet military and civilian dead was more than twice the death toll of all Americans, Britons, Commonwealth, French and even Germans killed in the war combined…. According to British military historian Anthony Bevoir, 1.1 million Soviet soldiers died in the Battle of Stalingrad and that does not include the at least 100,000 and possibly three times as many civilian inhabitants of the city massacred by the repeated waves of indiscriminate Luftwaffe air attacks….Nazi losses were colossal, too. According to Russian estimates, 1.5 million German and Axis soldiers lost their lives in the entire campaign, more than five times the entire U.S. combat dead for all of the war and more than twice the combined Union and Confederate dead of the entire U.S. Civil War.”

The Russian triumph at Stalingrad rapidly led to a German retreat and the inevitable encirclement of Berlin by allied forces. Here’s the scene in the German film Downfall, where Hitler finally realises he is defeated in Berlin, and lets out his anger on his Generals. This is the original video, parodied so many times on Youtube ~ the film is excellent and English Soft Subs/Closed Captions are available, look at the bottom right. 4 minute video

My point here is that patriotism that is grounded in overcoming a foreign invader ~ such as Russia’s victory at Stalingrad ~ is far more formidable than just waving flags and singing anthems. America should be conscious that our illegal occupations of Iraq and Afghanistan have resulted in millions of civilian deaths and displacements. More importantly they have also become the breeding ground of patriotic freedom fighters who can no longer be labeled insurgents or terrorists ~ who we use to justify even more military spending.

And who is paying the cost of roughly 3 trillion dollars for these illegal wars and occupations?

American families are now paying at least $20,000 each for these occupations (including the hidden social costs) with no end in sight.

It’s the biggest bubble of all ~ The so-called US government takes our money;

Then gives it to corporate thieves and uses it to create mayhem around the world. We are poorer for it. Our children are poorer for it. The nation is poorer for it. It’s really no more complicated than that.

Now, 70 years later, the apparently invincible American Wehrmacht, as recently represented by Vice President Joe Biden, set the record straight at the annual Munich Security Conference ~ as reported by WSWS “.. not only is this decade-long exercise in US militarism not ended, it is about to erupt in a whole number of new areas across the globe, threatening the lives of countless millions of people.”

“The greatest threat to our world and its peace comes from those who want war, who prepare for it, and who, by holding out vague promises of future peace or by instilling fear of foreign aggression, try to make us accomplices to their plans.” ~ Hermann Hesse

In calling off Operation Sea Lion, Adolf Hitler, the Supreme Commander of the world's most powerful armed forces, had suffered his first major setback. Nazi Germany had stumbled in the skies over Britain but Hitler was not discouraged. In the past, he had repeatedly overcome setbacks of one sort or another through drastic action elsewhere to both triumph over the failure and to move toward his ultimate goal. Now it was time to do it again.

All of Hitler's actions in Western Europe thus far, including the subjugation of France and the now-failed attack on Britain, were simply a prelude to achieving his principal goal as Führer, the acquisition of Lebensraum (Living Space) in the East. He had moved against the French, British and others in the West only as a necessary measure to secure Germany's western border, thereby freeing him to attack in the East with full force.

For Hitler, the war itself was first and foremost a racial struggle and he viewed all aspects of the conflict in racial terms. He considered the peoples of Western Europe and the British Isles to be racial comrades, ranked among the higher order of humans. The supreme form of human, according to Hitler, was the Germanic person, characterized by his or her fair skin, blond hair and blue eyes. The lowest form, Hitler believed, were the Jews and the Slavic peoples of Eastern Europe, including the Russians.

All of this had been outlined in his book, Mein Kampf, first published in 1925. In it, Hitler stated his fundamental belief that Germany’s survival depended on its ability to acquire vast tracts of land in the East to provide room for the expanding German population at the expense of the inferior peoples already living there, justified purely on racial grounds. Hitler explained that Nazi racial philosophy “by no means believes in an equality of races…and feels itself obligated to promote the victory of the better and stronger, and demand the subordination of the inferior and weaker.”

Therefore, in stark contrast to the battles so far in the West, Hitler intended the quest for Lebensraum in the East to be a "war of annihilation" utilizing the might of the German Army and Air Force against soldiers and civilians alike.

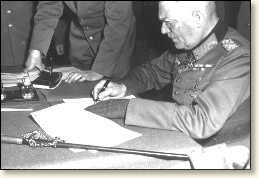

In March of 1941, he assembled his top generals and told them how their troops should behave: “This struggle is one of [political] ideologies and racial differences and will have to be conducted with unprecedented, unmerciful and unrelenting harshness. All officers will have to rid themselves of obsolete ideologies…I insist absolutely that my orders be executed without contradiction." Hitler then ordered the killing of all Russian political authorities. "The [Russian] commissars are the bearers of ideologies directly opposed to National Socialism. Therefore the commissars will be liquidated. German soldiers guilty of breaking international law…will be excused.” His generals listened in silence to this command, known later as the Commissar Order.

For his most senior generals, the utterances of their Supreme Commander posed a dilemma. They were mostly men of the old-school, born and raised in Imperial Germany, long before Hitler, amid traditional morals of bygone days. Now, they felt duty-bound to follow Hitler’s orders, no matter how drastic, since they had all sworn an oath of obedience to the Führer. But to comply, they would have to abandon time-honored codes of military conduct, considered obsolete by Hitler, which prohibited senseless murder of civilians.

At the same time, they each owed a debt of gratitude to Hitler for restoring the Germany Army to greatness and for the slew of promotions bestowed upon them by the Führer in the wake of its continued success. Rank and privilege, and the immense prestige of holding the title of Colonel-General or Field Marshal in Hitler's Wehrmacht, had tremendous appeal for these men, Therefore, in the end, despite their misgivings, not one of them dared to speak up or refuse Hitler in regard to his war plans for Russia. Instead, they dutifully planned the invasion of Russia, knowing the attack would unleash an unprecedented wave of murder.

The invasion plan for Russia was named Operation Barbarossa (Red Beard) by Hitler in honor of German ruler Frederick I, nicknamed Red Beard, who had orchestrated a ruthless attack on the Slavic peoples of the East some eight centuries earlier.

Barbarossa would be Blitzkrieg again but on a continental scale this time, as Hitler boasted to his generals, "When Barbarossa commences the world will hold its breath and make no comment!" Set to begin on May 15, 1941, three million soldiers totaling 160 divisions would plunge deep into Russia in three massive army groups, reaching the Volga River, east of Moscow, by the end of summer, thus achieving victory.

Facing them would be Stalin's Red Army, estimated by the Germans at 200 divisions. Although somewhat outnumbered by the Russians, Hitler believed they did not pose a serious threat and would fall apart just like their fellow Slavs, the Poles, did in 1939. Against an army of battle-hardened, racially superior Germans, the Russians would be finished in a matter of weeks, Hitler claimed.

Most of his generals concurred, supported by recent evidence. They had watched with keen interest as Soviet Russia confidently invaded Finland in November 1939, only to see the Red Army disintegrate into a disorganized jumble amid embarrassing defeats at the hands of a much smaller blond-haired Finnish fighting force.

Buoyed by Hitler and awash in their own arrogance, the generals confidently finalized the details of Operation Barbarossa as the bulk of the German troops and armor slowly moved into position in the weeks leading up to May 15. But as the invasion date neared, complications arose that upset the whole timetable.

Hitler's old friend and chief ally, Benito Mussolini, leader of Fascist Italy, had foolishly tried to imitate the Führer and achieve battlefield glory for himself by launching a surprise invasion of Greece. British troops stationed in the Mediterranean then moved in to help the Greeks fend off the Italians. For Hitler, the very idea of British troops in Southern Europe was enough to keep him awake at night. Their presence was a threat to Germany's vulnerable southern flank, the region of Europe known as the Balkans, which also supplied most of Germany's oil. It would therefore be necessary to secure the Balkans before launching Barbarossa.

To quickly achieve this, Hitler slipped back into a familiar role – the political master manipulator – forging overnight alliances with two Balkan countries, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia.

But in Yugoslavia, things unexpectedly spiraled out of control when the government, upon its alliance with Hitler, was immediately overthrown by its own citizens. Hitler was enraged by the news, perceiving it as a blow to his prestige. In a tirade, he ordered his generals to crush the country "as speedily as possible" and also ordered Göring's Air Force to obliterate the capital city, Belgrade, as "punishment." For the Luftwaffe, Belgrade was an easy target and they quickly turned it to rubble while killing 17,000 defenseless civilians.

Meanwhile, beginning on Sunday, April 6, 1941, the Wehrmacht poured 29 divisions into the region, taking Yugoslavia by storm, then took Greece for good measure, forcing British troops there to make a hasty exit. Thus the Balkans were secured. However, these actions took nearly five weeks and caused a lot of wear and tear on tanks and other armored equipment needed for the Russian campaign.

July 1941. A confident looking Hitler with Luftwaffe Chief Hermann Göring (right) and a decorated fighter pilot. Behind Hitler is his chief military aide Wilhelm Keitel, now a Field Marshal. Below: General Heinz Guderian in Russia, full of confidence as well.

The new launch date for Barbarossa was Sunday, June 22, 1941. On that day, beginning at 3:15 am, 3.2 million Germans plunged headlong into Russia across an 1800-mile front, taking their foes by surprise. Russian field commanders made frantic calls to headquarters asking for orders, but were told there were no orders. Sleepy-eyed infantrymen scrambled out of their tents to find themselves already surrounded by Germans, with no option but to surrender. Bridges were captured intact while hundreds of Russian planes were destroyed sitting on the ground.

At 7 am that morning, over the radio, a proclamation from the Führer to the German people announced, “At this moment a march is taking place that, for its extent, compares with the greatest the world has ever seen. I have decided again today to place the fate and future of the Reich and our people in the hands of our soldiers. May God aid us, especially in this fight.”

In attacking Russia, Hitler had indeed stunned the world. But he also made a lot of Germans very nervous. Maria Mauth, a 17-year-old German schoolgirl at the time, recalled her father's reaction: "I will never forget my father saying: 'Right, now we have lost the war!' " But then reports arrived highlighting the easy successes. "In the weekly newsreels we would see glorious pictures of the German Army with all the soldiers singing and waving and cheering. And that was infectious of course...We simply thought it would be similar to what it was like in France or in Poland – everybody was convinced of that, considering the fabulous army we had."

Indeed, it was true. Whole armies of hapless Russians were now surrendering as the relentless three-pronged Blitzkrieg blasted its way forward. Soviet Russia had been caught unprepared due to the astounding negligence of the country's dictator, Josef Stalin, who had stubbornly disregarded a flurry of intelligence reports warning that a Nazi invasion was imminent.

The result was chaos. Georgy Semenyak, a 20-year-old Russian soldier at the time, remembered: “It was a dismal picture. During the day airplanes continuously dropped bombs on the retreating soldiers…When the order was given for the retreat, there were huge numbers of people heading in every direction…The lieutenants, captains, second-lieutenants took rides on passing vehicles…mostly trucks traveling eastwards…And without commanders, our ability to defend ourselves was so severely weakened that there was really nothing we could do.”

Hitler and the Army High Command were now poised to achieve the greatest military victory of all time by trouncing the Russians. At present, three gigantic army groups were proceeding like clockwork toward their objectives. Army Group North, with 20 infantry divisions and six armored divisions, headed for Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) by the Baltic Sea. Army Group Center, the largest, with 33 infantry and 15 armored divisions, continued on its 700-mile-long journey toward Russia’s capital, Moscow. Army Group South, with 33 infantry and eight armored divisions, headed for Kiev, capital of the Ukraine, the breadbasket of Europe with its fertile wheat fields. Along the way, German field commanders employed their already-perfected Blitzkrieg techniques time and time again to pierce Russian defensive lines and surround bewildered Red Army soldiers.

June 1941 - Barbarossa

German invasion of the Soviet Union that opened World War II on the Eastern Front, commencing the largest, most bitterly contested, and bloodiest campaign of the war. Adolf Hitler’s objective for Operation BARBAROSSA was simple: he sought to crush the Soviet Union in one swift blow. With the USSR defeated and its vast resources at his disposal, surely Britain would have to sue for peace. So confident was he of victory that he made no effort to coordinate the invasion with his Japanese ally. Hitler predicted a quick victory in a campaign of, at most, three months.

German success hinged on the speed of advance of 154 German and satellite divisions deployed in three army groups: Army Group North in East Prussia, under Field Marshal Wilhelm von Leeb; Army Group Center in northern Poland, commanded by Field Marshal Fedor von Bock; and Army Group South in southern Poland and Romania under Field Marshal Karl Gerd von Rundstedt. Army Group North consisted of 3 panzer, 3 motorized, and 24 infantry divisions supported by the Luftflotte 1 and joined by Finnish forces. Farther north, German General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst’s Norway Army would carry out an offensive against Murmansk in order to sever its supply route to Leningrad. Within Army Group Center were 9 panzer, 7 motorized, and 34 infantry divisions, with the Luftflotte 2 in support. Marshal von Rundstedt’s Army Group South consisted of 5 panzer, 3 motorized, and 35 infantry divisions, along with 3 Italian divisions, 2 Romanian armies, and Hungarian and Slovak units. Luftflotte 4 provided air support.

Meeting this onslaught were 170 Soviet divisions organized into three “strategic axes” (commanding multiple fronts, the equivalent of army groups)—Northern, Central, and Southern or Ukrainian—that would come to be commanded by Marshals Kliment E. Voroshilov, Semen K. Timoshenko, and Semen M. Budenny, respectively. Voroshilov’s fronts were responsible for the defense of Leningrad, Karelia, and the recently acquired Baltic states. Timoshenko’s fronts protected the approaches to Smolensk and Moscow. And those of Budenny guarded the Ukraine. For the most part, these forces were largely unmechanized and were arrayed in three linear defensive echelons, the first as far as 30 miles from the border and the last as much as 180 miles back.

In World War 2, Hitler and Stalin, two of the most brutal dictators ever, commanded total control and led murderous terror regimes, in which fear of extreme punishment made it almost impossible to criticize or even to offer unfavorable advice, or even to awake the dictator late at night in case of emergency. In such regimes, one man makes all key decisions, and too many lesser decisions, and it's almost impossible to change his mind before or after he makes a major mistake. Here are some examples.

Full-scale development of the LaG-5, as the aircraft was now designated, began, and simultaneously problems arose concerning the initiation of the production process. Especially difficult to build were the first ten aircraft, assembled early in June 1942, which were manufactured in dreadful haste, with numerous errors. While it is normal practice to make parts from drawings, this time, on the contrary, final drawings were sometimes made from the parts. At the same time the tooling was being prepared and the process of producing new components was being mastered.

Aircraft Plant No.21 handled the task well. The transition to the modified fighter was effected almost without any reduction in the delivery rate to the air force. Following delivery of the first fully operational LaG-5 on 20th June 1942, the Gorkii workers turned out 37 more by the end of the month. In August the plant surpassed the production rate of all the previous months, 148 LaGG-3s being added to 145 new LaG-5s.

Series produced aircraft were considerably inferior to the prototype in speed, being some 24.8 to 31 mph (40 to 50km/h) slower. On the one hand this is understandable, as the LaGG-3 M-82 prototype lacked the radio antenna, bomb carriers and leading edge slats fitted to production aircraft. But there were other contributory causes, particularly insufficiently tight cowlings. Work carried out by Professor V Polinovsky with the workers of the design bureau of Plant No.21 enabled the openings to be found and eliminated.

Series built aircraft were sent to war, and the LaG-5's combat performance was proved in the 49th Red Banner Fighter Air Regiment of the 1st Air Army. In the unit's first 17 battles 16 enemy aircraft were shot down at a cost of ten of its own, five pilots being lost. Command believed that the heavy losses occurred because the new aircraft had not been fully mastered and, as a consequence, its operational qualities were not used to full advantage. Pilots noted that, owing to the machine's high weight and insufficient control surface balance, it made more demands upon flying technique than the LaGG-3 and Yak-1. At the same time, however, the LaG-5 had an advantage over fighters with liquid-cooled engines, as its double-row radial protected its pilot from frontal attacks. Aircraft survivability increased noticeably as a consequence. Three fighters returned to their airfield despite pierced inlet nozzles, exhaust pipes and rocker box covers.

The involvement of LaG-5s of the 287th Fighter Air Division, commanded by Colonel S Danilov, Hero of the Soviet Union, in the Battle of Stalingrad was a severe test for the aircraft. Fierce fighting took place over the Volga, and the Luftwaffe was stronger than ever before. The division experienced its first combats on 20th August 1942 with 57 LaG-5s, of which two-thirds were combat capable. Four regiments of the division were to have 80 fighters on strength, but a great many deficiencies prevented this. Serious accidents occurred; one fighter crashed during take-off, and two more collided while taxying owing to the pilots' poor view. During the first three flying days the LaGs shot down eight German fighters and three bombers. Seven were lost, including three to 'friendly' anti-aircraft fire.

Subsequently, the division pilots were more successful. There were repeated observations of attacks against enemy bombers, of which 57 were destroyed within a month, but the division's own losses were severe.

Based on experience gained during combat, the pilots of the 27th Fighter Air Regiment, 287th Fighter Air Division, concluded that their fighters were inferior to Bf109F-4s and, especially, 'G-2s in speed and vertical manoeuvrability. They reported: 'We have to engage only in defensive combat actions. The enemy is superior in altitude and, therefore, has a more favourable position from which to attack.'

Hitherto, it has often been stated in Soviet and other historical accounts that the La-5 (the designation assigned to the fighter in early September 1942) had passed its service tests during the Stalingrad battle in splendid fashion. In reality, this advanced fighter still had to overcome some 'growing pains'.

This was proved by state tests of the La-5 Series 4 at the NII WS during September and October 1942. At a flying weight of 7,4071b (3,360kg) the aircraft attained a maximum speed at ground level of 316mph (509km/h) at its normal power rating, 332.4mph (535 km/h) at its augmented rating and 360.4mph (580km/h) at the service ceiling of 20,500ft (6,250m) The Soviet-made M-82 family of engines - derived from the US-designed Wright R-1820 Cyclone - had an augmented power rating only at the first supercharger speed). The aircraft climbed to 16,400ft (5,000m) in 6.0 minutes at normal power rating and in 5.7 minutes with augmentation. Its armament was similar to that of the prototype. Horizontal manoeuvrability was slightly improved, but in the vertical plane it was decreased. Many defects in design and manufacture had not been corrected.

In combat Soviet pilots flew the La-5 with the canopy open, the cowling side flaps fully open and the tailwheel down, and this reduced its speed by another 18.6 to 24.8mph (30 to 40km/h). As a result, on 25th September 1942 the State Defence Committee issued an edict requiring that the La-5 be lightened, and that its performance and operational characteristics be improved.

The industry produced 1,129 La-5s during the second half of 1942, and these saw use during the counter attack by Soviet troops near Stalingrad. Of 289 La-5s in service with fighter aviation, the majority, 180 aircraft, were assigned to the forces of the Supreme Command Headquarters Reserve. The Soviet Command was preparing for a general winter offensive, and was building up reserves to place in support. One of these strong formations became the 2nd Mixed Air Corps under Hero of the Soviet Union Major-General I Yeryomenko, the two fighter divisions of which had five regiments (the 13th, 181st, 239th, 437th and 3rd Guards) equipped with the improved La-5. The new aircraft proved to be 11 to 12.4mph (18 to 20km/h) faster than the fighter which had passed the state tests at the NII WS in September and October 1942.

When the 2nd Mixed Air Corps, with more than 300 first class combat aircraft, was used to reinforce the 8th Air Army, the latter had only 160 serviceable aircraft. The 2nd Mixed Air Corps, reliably protecting and supporting the counter offensive by troops along the lines of advance, flew over 8,000 missions and shot down 353 enemy aircraft from 19th November 1942 to 2nd February 1943.

Progress made in combat activities by the Air Corps aviators in co-operation with joint forces during offensive operations on the Stalingrad and Southern fronts were noted by the ground forces Command. General Rodion Malinovsky, Commander of the 2nd Guards Army (later Defence Minister), wrote:

'The active warfare of the fighter units of the 2nd Mixed Air Corps [of which 80% of its aircraft were La-5s], by covering and supporting combat formations of Army troops, actually helped to protect the army from enemy air attacks. Pilots displayed courage, heroism and valour in the battlefield. With appearance of the Air Corps fighters the hostile aircraft avoided battle.

These men are Russian officers in the ROA, the Russian Liberation Army (In Russian: Russkaya Osvoboditelnaya Armiya). They are a part of captured Russian soldiers who joined the Germans and their Allies in the struggle against Bolshevism. The officer second from the left is General Vlasov. The ROA consisted of two divisions under the command of General Vlasov and its popular name was Vlasov's army.

By 1944 defeat stared Germany in the face. Goebbels's propaganda machine did its best to counter the deterioration of morale, especially emphasizing the bleak prospects with which the "unconditional surrender" slogan confronted the German people. On July 20 a few army officers and government officials attempted to kill Hitler and overthrow the Nazi regime, but the plot miscarried and merely resulted in the liquidation of the chief non-Nazis anywhere near the summit of power.

Opportunely for Goebbels came Allied publication of lists of "war criminals," the mass proscription of the German General Staff, and the approval of the "Morgenthau Plan," which envisaged the destruction of German industry and the conversion of all Germany into "a country primarily agricultural and pastoral in character," at the second Quebec conference in September 1944. Goebbels declared, "It hardly matters whether the Bolshevists want to destroy the Reich in one fashion and the Anglo-Saxons propose to do it in another." Doubtless the Morgenthau Plan did much to confuse those Germans who might be thinking of surrendering to the West while holding out against Stalin,, and thus Stalin could only profit by its dissemination by the U.S. and Britain.

At virtually the same moment that the Allies were endorsing the Morgenthau Plan at Quebec, the Nazi regime turned in desperation to a weapon which, if used earlier, might indeed have had great effect on the outcome of the war, but what the Nazis did with it in 1944 was too little and much too late. General Vlasov, who had been captured two years earlier, was to be transformed from a pawn of Nazi propaganda into the leader of a real Soviet anti-Stalinite army and government.

Vlasov, who was born in 1900, the son of a peasant family of Nizhnii Novgorod, had risen in Red Army ranks. A Party member since 1930, he had been Soviet military adviser to Chiang Kai-shek in 1938-1939, decorated in 1940, and in the autumn of 1941 one of the chief army commanders in the defense of Moscow. Apparently he possessed great personal magnetism, integrity, and ability. Not at all the opportunist and Nazi hireling he was accused of being, Vlasov "stressed his nationalism and strove to preserve the independence of the Movement," writes the most recent Investigator. Of the most influential men who joined his cause, probably the ablest was the brilliant but mysterious Milenty Zykov, who said he had been on the staff of Izvestiia under Bukharin and for a time had been exiled by Stalin. When captured he claimed to be serving as a battalion commissar, but it was suspected that he was much more.

By the end of 1942 Captain Wilfried Strik-Strikfeldt of the German army propaganda section was planning to establish a Russian National Committee led by Vlasov at Smolensk. The plan was vetoed from above, but in December the formation of the committee was proclaimed on German soil Instead. Vlasov published a statement of his aims, and he was allowed to tour occupied Soviet areas, meeting a considerable popular response. In April 1943 an anti-Bolshevik conference of Soviet prisoners opposed to Stalin's regime was held in Brest-Litovsk. After Vlasov declared that if successful he would grant Ukraine and the Caucasus self-determination, Rosenberg was persuaded to support the committee. However, in June 1943 Hitler ordered that Vlasov was to be kept out of the occupation zone, and that the movement was to be confined to propaganda—that is, promises which Hitler could ignore later—across the lines to Soviet-held territory.

During 1943 Vlasov's circle, under the protection of Strik-Strikfeldt's section at Dabendorf just outside Berlin, was allowed to carry on remarkably free discussions about a future non-Communist government for Russia and to publish two newspapers in Russian, one for Soviet war prisoners and another for the Osttruppen. The political center of gravity at Dabendorf fluctuated between the more socialist-inclined entourage of Zykov and the more authoritarian-minded group close to the emigre anti-Soviet organization, N.T.S. (Natsionalno-Trudovoi Soiuz or National Tollers' Union). Of course political arguments among Soviet emigres were nothing new; what was new was the hope of imminent action, utilizing the five million Soviet nationals in Germany, to overthrow Stalin—either with Hitler's support or, if he should fall, perhaps in conjunction with the Western Allies. Despite arguments, a fair degree of harmony was maintained among the Russians at Dabendorf. Especially noteworthy was the extent to which Vlasov and his followers succeeded in preventing themselves from being compromised by Nazi Ideology and in maintaining the integrity of their own effort to win Russian freedom.

Until 1944, however, the Vlasov circle was confined to discussion and publication. Although the phrase, "Russian Liberation Army," and Its Russian abbreviation, ROA (for Russkaia Osvoboditel'naia Armiia), were much used in propaganda— with Hitler's approval—there was in fact no such army. "ROA" was only a shoulder patch which the Osttruppen, scattered in small units throughout the Nazi army, were permitted to wear. In the summer of 1944 the ablest Intellectual of the Vlasov group, Zykov, was abducted and almost certainly murdered forthwith by the SS.

Nevertheless it was Himmler, chief of the SS, who not long afterward achieved the reversal of Nazi policy toward Vlasov. In a meeting with Vlasov in mid-September 1944, Himmler agreed to the formation of a Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia (Komitet Osvobozhdeniia Narodov Rossii or K.O.N.R.), which would have the potentiality of a government, and an actual army. It appears that Hitler consented to Himmler's new policy chiefly because his suspicion of other Nazi officials who opposed it was by 1944 greater than his fear of arming enemy nationals—a fear which, it must be said, was justified from the Nazi standpoint. The concrete results of Himmler's decision were meager, largely because the Russians could not, amid the disintegration which overtook the Nazi system during the last months of the war, obtain the material aid they needed to implement their plans.

However, in November 1944 in Prague the K.O.N.R. was officially established at a meeting which issued the so-called "Prague Manifesto." This document, declaring that the irruption of the Red armies into Eastern Europe revealed more clearly than ever the Soviet "aim to strengthen still more the mastery of Stalin's tyranny over the peoples of the USSR, and to establish it all over the world," stated the goals of the K.O.N.R. to be the overthrow of the Communist regime and the "creation of a new free People's political system without Bolsheviks and exploiters." It proclaimed recognition of the "equality of all peoples of Russia" and their right of self-determination as well as the intention of ending forced labor and the collective farms and of achieving real civil liberties and social justice. If such a document had been widely disseminated two or three years earlier and given some substance in Nazi occupation policy, the results might have been important or even decisive; coming in 1944, it had no observable effect on the Soviet peoples.

The Prague meeting did stimulate certain Nazi officials to make efforts to put the minorities into the picture with political committees and armies. A year earlier the Nazis had finally organized a Ukrainian SS division which bore the name "Galicia," but although it fought hard and well at the battle of Brody, on the Rovno-Lvov road, in July 1944, when it was finally overrun there, it dispersed to join Ukrainian partisan forces behind Red lines. In October an SS official, Dr. Fritz Arlt, attempted to secure the consent of the Ukrainian nationalist leaders to the formation of a Ukrainian national committee. To avoid being overshadowed by Vlasov, Bandera and Melnyk agreed to the setting up of such a committee, nominally headed by General Paul Shandruk. Melnyk protested the Prague Manifesto, but many Ukrainians nevertheless joined the Vlasov movement, along with representatives of other minorities.

In January 1945 the formation of the Armed Forces of the K.O.N.R. was announced; however, only two divisions were actually activated and mobilized. The First Division, under the command of a Ukrainian, General S. K. Buniachenko, was committed in April on the front near Frankfurt on the Oder, but the unit refused to fight under existing circumstances, and amid the Nazi military collapse moved south toward Czechoslovakia. At the call of the Czech resistance leaders in Prague, the division moved into the city and on May 7, with Czech aid, captured it from the Nazis.

However, in the Europe of the spring of 1945 there was no place for an anti-Soviet Russian army. The generals, including Vlasov, were turned over to the Soviet command by American and British forces, with or without authorization to do so. In February 1946 the remainder of the army was handed over by U.S. authorities without warning to Soviet repatriation officers at Plattling, Bavaria. In August Pravda announced the execution of Vlasov and his fellow officers, describing them as "agents of German intelligence" and failing to inform the Russian people that they had organized a movement to overthrow Stalin.

By mid-July 1941, all that remained was for the Russians to give up and accept their fate under Hitler, just like Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Norway, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland, France, Yugoslavia, and Greece.

But the Russians kept fighting.

October 1941. German infantrymen plunge ever deeper into Russia. Below: Hitler at the map table with Army Commander-in-Chief Brauchitsch and others, including Friedrich Paulus (2nd from left).

Despite staggering losses of men and equipment, pockets of fanatical resistance now emerged, unlike anything the Germans had encountered thus far in the war. And there were more surprises for the Germans. They had grossly underestimated the total fighting strength of the Red Army. Instead of 200 divisions, the Russians could field 400 divisions when fully mobilized. This meant there were three million additional Russians available to fight.

Another emerging factor was the vastness of Russia itself. It was one thing to ponder a map, something else to traverse the boundless countryside, as Field Marshal Manstein remembered: "Everyone was captivated at one time or other by the endlessness of the landscape, through which it was possible to drive for hours on end – often guided by the compass – without encountering the least rise in the ground or setting eyes on a single human being or habitation. The distant horizon seemed like some mountain ridge behind which a paradise might beckon, but it only stretched on and on."

The vastness created logistical problems including worn out foot soldiers and dangerously overstretched supply lines. It also taxed the ability of the Luftwaffe to provide close cover for advancing ground troops, a vital ingredient in the Blitzkrieg formula.

On top of this, Russian resistance began to stiffen all over as the soldiers and people rallied behind Stalin in the defense of their Motherland. Stalin, at first overwhelmed by the magnitude of Barbarossa, had regained his bearings and publicly appealed for a "Great Patriotic War" against the Nazi invaders. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, he enacted ruthless measures, executing his top commander in the west and various field commanders who had been too eager to retreat.

Under Stalin's tight-fisted grip, the chaos and panic that had initially enveloped the Russian officer corps gradually subsided. Red Army commanders took heed from Stalin, instilling his 'fight to the death' mentality in their frontline soldiers. They set up new defensive positions, not to be yielded until every last soldier was killed. They also began their first-ever counter-attacks against the advancing Germans.

As a result, with each passing day the Germans began to lose momentum. They could no longer easily blow through the Russian defenses and had to be wary of counter-strikes. All the while, German foot soldiers were becoming increasingly fatigued. By August of 1941, it had become apparent to the Army High Command there would be no speedy victory. “The whole situation makes it increasingly plain that we have underestimated the Russian colossus,” General Franz Halder, Chief of the General Staff, had to admit.

Therefore the question now arose – what to do – follow the original battle plan for Barbarossa or make changes to adapt?

Army Group Center was presently about 200 miles from Moscow, poised for a massive assault. However, the original plan called for Army Groups North and South to stage the main attacks in Russia, with Army Group Center playing a supporting role until their tasks were completed, after which Moscow would be taken.

A majority of Hitler’s senior generals now implored him to scrap Barbarossa in favor of an all-out attack on Moscow. If the Russian capital fell, they argued, it would devastate Russian morale and knock out the country’s chief transportation hub. Russia’s days would surely be numbered.

The decision rested solely with the Supreme Commander.

In what was perhaps his single biggest decision of World War II, Hitler passed up the chance to attack Moscow during the summer of 1941. Instead, he clung to the original plan to crush Leningrad in the north and simultaneously seize the Ukraine in the south. This, Hitler lectured his generals, would be far more devastating to the Russians than the fall of Moscow. A successful attack in the north would wreck the city named after one of the founders of Soviet Russia, Vladimir Lenin. Attacking the south would destroy the Russian armies protecting the region and place vital agricultural and industrial areas in German hands.

Though they remained unconvinced, the generals dutifully halted the advance on Moscow and repositioned troops and tanks away from Army Group Center to aid Army Groups North and South. By late September, bolstered by the additional Panzer tanks, Army Group South successfully captured the city of Kiev in the Ukraine, taking 650,000 Russian prisoners. As Army Group North approached Leningrad, a beautiful old city with palaces that once belonged to the Czars, Hitler ordered the place flattened via massive aerial and artillery bombardments. Concerning the five million trapped inhabitants, he told his generals, “The problem of the survival of the population and of supplying it with food is one which cannot and should not be solved by us.”

Now, with Leningrad surrounded and the Ukraine almost taken, the generals implored Hitler to let them take Moscow before the onset of winter. This time Hitler consented, but only partly. He would allow an attack on Moscow, provided that Army Group North also completed the capture of Leningrad, while Army Group South advanced deeper into southern Russia toward Stalingrad, the city on the Volga River named after the Soviet dictator.

This meant German forces in Russia would be attacking simultaneously on three major fronts over two thousand miles long, stretching their manpower and resources to the absolute limit. Realizing the danger, the generals pleaded once more for permission to focus on Moscow alone and strike the city with overwhelming force. But Hitler said no.

In the meantime, German troops still holding outside Moscow had remained idle for nearly two months, waiting for orders to advance. When the push finally began on October 2, 1941, a noticeable chill already hung in the morning air, and in a few places, snowflakes wafted from the sky. The notorious Russian winter was just around the corner.

At first it appeared Moscow might be another easy success. Two Russian army groups defending the main approach were quickly encircled and broken up by motorized Germans who took 660,000 prisoners.

Confident the war in Russia was just about won, Hitler took a leap by announcing victory to the German people: “I declare today, and I declare it without any reservation, that the enemy in the East has been struck down and will never rise again…Behind our troops already lies a territory twice the size of the German Reich when I came to power in 1933.”

By mid-October, forward German units had advanced to within 40 miles of Moscow. Only 90,000 Russian soldiers stood between the German armies and the Soviet capital. The entire government, including Stalin himself, prepared to evacuate.

But then the weather turned.

Russian Winter. Near Moscow, a wounded German is rescued. Below: A Panzer III tank stuck in the snow and cold as the whole offensive stalls.

It began with weeks of unending autumn rain, creating battlefields of deep, sticky mud that immobilized anything on wheels and robbed German armored units of their tactical advantage. The non-stop rain drenched foot soldiers, soaking them to the bone in mud up to their knees. And things only got worse. In November, autumn rains abruptly gave way to snow squalls with frigid winds and sub-zero temperatures, causing frostbite and other cold-related sickness.

The German Army had counted on a quick summertime victory in Russia and had therefore neglected to prepare for the brutal winter warfare it now faced. German medical officer Heinrich Haape recalled: “The cold relentlessly crept into our bodies, our blood, our brains. Even the sun seemed to radiate a steely cold and at night the blood red skies above the burning villages merely hinted a mockery of warmth.”

Heavy boots, overcoats, blankets and thick socks were desperately needed but were unavailable. As a result, thousands of frostbitten soldiers dropped out of their frontline units. Some divisions fell to fifty-percent of their fighting strength. Food supplies also ran low and the troops became malnourished. Mechanical failures worsened as tank and truck engines cracked from the cold while iced-up artillery and machine-guns jammed.

The once-mighty German military machine had now ground to a halt in Russia.

Frontline Russians noticed the change. A Soviet commander in the 19th Rifle Brigade recalled: "I remember very well the Germans in July 1941. They were confident, strong tall guys. They marched ahead with their sleeves rolled up and carrying their machine-guns. But later on they became miserable, crooked, snotty guys wrapped in woolen kerchiefs stolen from old women in villages...Of course, they were still firing and defending themselves, but they weren't the Germans we knew earlier in 1941."

Ignoring the plight of his frontline soldiers, Hitler insisted that Moscow could still be taken and ordered all available troops in the region to make one final thrust for victory. Beginning on December 1, 1941, German tank formations attacked from the north and south of the city while infantrymen moved in from the east. But the Russians were ready and waiting. The weather delays had given them time to bring in massive reinforcements, including 30 Siberian divisions specially trained for winter warfare. Wherever the Germans struck they encountered fierce resistance and faltered. They were also stricken by temperatures that plunged to 40 degrees below zero at night.

Hitler had pushed his troops beyond human endurance and now they paid a terrible price. On Saturday, December 6th, a hundred Russian divisions under the command of the Red Army's new leader, General Georgi Zhukov, counter-attacked the Germans all along the 200-mile front around Moscow. For the first time in the war, the Germans experienced Blitzkrieg in reverse, as overwhelming numbers of Russian tanks, planes and artillery tore them apart. The impact was devastating. By mid-December, German forces around Moscow, battered, cold and tremendously fatigued, were in full retreat and facing the possibility of being routed by the Russians.

Just six months earlier, the Germans had been poised to achieve the greatest victory of all time and change world history. Instead, they had succumbed to the greatest-ever comeback by their Russian foes. By now a quarter of all German troops in Russia, some 750,000 men, were either dead, wounded, missing or ill.

Reacting to the catastrophe he had caused, Hitler blamed the Wehrmacht's leadership, dismissing dozens of field commanders and senior generals, including Walther von Brauchitsch, Commander-in-Chief of the Army. Hitler then took that rank for himself, assuming personal day-to-day operational command of the Army, and promptly ordered all surviving troops in Russia to halt in their tracks and retreat not one step further, which they did. As a result, the Eastern Front gradually stabilized.

In the bloodied fields of snow around Moscow, Adolf Hitler had suffered a breathtaking defeat. The German Army would never be the same. The illusion of invincibility that had caused the world to shudder in the face of Nazi Germany had vanished forever – replaced now by a sliver of hope.

But for the populations of Eastern Europe and occupied Russia, there was much suffering yet to be endured. In cities and villages behind the front lines, Hitler's war of annihilation was fully underway, comprising the most savage episode in human history.

Because of his experiences in Vienna, World War One, the Münich putsch and in prison, Adolf Hitler dreamed of building a vast German Empire sprawling across Central and Eastern Europe. Lebensraum could only be obtained and sustained by waging a war of conquest against the Soviet Union: German security demanded it and Hitler's racial ideology required it. War, then, was essential. It was essential to Hitler the man as well as essential to Hitler's dream of a new Germany. In the end, most historians have reached the consensus that World War Two was Hitler's war (for more on Hitler, see Lecture 9 and Lecture 10). Unfortunately, although most western statesmen had sufficient warning that Hitler was a threat to a general European peace, they failed to rally their people and take a stand until it was too late.

Following 1933 -- the year when Hitler consolidated his power as Chancellor through the Enabling Act -- Hitler implemented his foreign policy objectives. These objectives clearly violated the provisions of the Versailles Treaty. Hitler's foreign policy aims accorded with the goals of Germany's traditional rulers in that the aim was to make Germany the most powerful state in all of Europe. For example, during World War One, German generals tried to conquer extensive regions in Eastern Europe. And with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1918) between Germany and Russia, Germany took Poland, the Ukraine and the Baltic States from Russia. However, where Hitler departed from this traditional scenario was his obsession with racial supremacy. His desire to annihilate whole races of inferior peoples marked a break from the outlook of the old order. This old order never contemplated the restriction of the civil rights of the Jews. They wanted to Germanize German Poles, not enslave them.

But Hitler was an opportunist -- he was a man possessed and driven by a fanaticism that saw his destiny as identical to Germany's. The propaganda machine that Hitler adopted, however, was perhaps the most important device at his disposal. With it he was able to successfully undermine his opponent's will to resist. And propaganda, after winning the minds of the German people, now became a most crucial instrument of German foreign policy as a whole. There were upwards of 27 million German people living outside the borders of the Reich. To force those 27 million into support for Hitler, the Nazis utilized their propaganda machine. For example, they made every effort to export anti-Semitism internationally, thus feeding off prejudices of other nations. Hitler also began to promote himself as Europe's best defense against Stalin, the Bolsheviks and the Soviet Union (on Stalin see Lecture 10). In fact, the Nazi anti-Bolshevik propaganda convinced thousands of Europeans that Hitler was also Europe's best defense against all Communists.

|

Hitler used the threat of force to obtain Austria and a similar threat would give him the Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia. More than three-quarters of the population of the Sudetenland were ethnic Germans. The area also contained key industries and was vital to the protection of Czechoslovakia. Without this area heavily fortified Czechoslovakia could not hope to withstand German aggression. Sudentenland Germans, encouraged by the Nazis, began to denounce the Czech government. Meanwhile, Hitler's propaganda machine accused the Czech government of hideous crimes and warned of retribution. He ordered his generals to plan an invasion of Czechoslovakia. At this point, the British Prime Minister NEVILLE CHAMBERLAIN decided to intervene and Hitler agreed to a conference with him. The opinion of British statesmen was that the Sudetenland Germans were being deprived of their right to self-determination. The Sudetenland, like Austria, was not worth another war, they reasoned. Once the Germans were living under the German flag, the British argued, Hitler would be satisfied. And so the fate of Czechoslovakia was sealed in September 1938.

Hitler used the threat of force to obtain Austria and a similar threat would give him the Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia. More than three-quarters of the population of the Sudetenland were ethnic Germans. The area also contained key industries and was vital to the protection of Czechoslovakia. Without this area heavily fortified Czechoslovakia could not hope to withstand German aggression. Sudentenland Germans, encouraged by the Nazis, began to denounce the Czech government. Meanwhile, Hitler's propaganda machine accused the Czech government of hideous crimes and warned of retribution. He ordered his generals to plan an invasion of Czechoslovakia. At this point, the British Prime Minister NEVILLE CHAMBERLAIN decided to intervene and Hitler agreed to a conference with him. The opinion of British statesmen was that the Sudetenland Germans were being deprived of their right to self-determination. The Sudetenland, like Austria, was not worth another war, they reasoned. Once the Germans were living under the German flag, the British argued, Hitler would be satisfied. And so the fate of Czechoslovakia was sealed in September 1938. Chamberlain, Hitler, Mussolini and Daladier, the Prime Minister of France, signed the MÜNICH PACT and agreed that all Czech troops in the Sudetenland would be replaced by German troops. The British hailed Chamberlain -- the French hailed Daladier. While Chamberlain returned to England with a piece of paper in his hand, Hitler was laughing. What Britain and France had shown was their own weakness and this weakness increased Hitler's appetite for even more territory. With the Sudetenland annexed, Hitler plotted to annihilate the independent existence of Czechoslovakia. And so, in March 1939, Czechoslovak independence came to an end. After Czechoslovakia, Germany turned to Poland. Hitler demanded that the Polish port town of Danzig be returned to Germany. Poland refused to hand over Danzig since it was vital to their economy. Meanwhile, France and Britain warned Hitler that they would come to the assistance of Poland. On May 22, 1939, Hitler and Mussolini signed the Pact of Steel and promised one another mutual aid. One month later, the German army presented Hitler with battle plans for the invasion of Poland.

Chamberlain, Hitler, Mussolini and Daladier, the Prime Minister of France, signed the MÜNICH PACT and agreed that all Czech troops in the Sudetenland would be replaced by German troops. The British hailed Chamberlain -- the French hailed Daladier. While Chamberlain returned to England with a piece of paper in his hand, Hitler was laughing. What Britain and France had shown was their own weakness and this weakness increased Hitler's appetite for even more territory. With the Sudetenland annexed, Hitler plotted to annihilate the independent existence of Czechoslovakia. And so, in March 1939, Czechoslovak independence came to an end. After Czechoslovakia, Germany turned to Poland. Hitler demanded that the Polish port town of Danzig be returned to Germany. Poland refused to hand over Danzig since it was vital to their economy. Meanwhile, France and Britain warned Hitler that they would come to the assistance of Poland. On May 22, 1939, Hitler and Mussolini signed the Pact of Steel and promised one another mutual aid. One month later, the German army presented Hitler with battle plans for the invasion of Poland. While all this was going on, negotiations were under way between Britain, France and Russia. The Soviets wanted mutual aid -- but they also demanded military bases in Poland and Romania. Britain would not give in to their demands. And of course, while all this is going on, Russia was conducting secret talks with Germany. The result of all this was that on August 23, 1939, Ribbentrop and Molotov signed the NAZI-SOVIET PACT of non-aggression. One section of this Pact -- even more secret than the Nazi-Soviet Pact itself -- called for the partition of Poland between Germany and Russia. The Nazi-Soviet pact served as the green light for the invasion of Poland and on September 1, 1939, German troops marched into Poland. Britain and France demanded that Hitler stop his forces but Hitler ignored them and so Britain and France declared war on Germany. Using the Blitzkrieg or lightening war, Poland succumbed to Germany on September 27, 1939.

While all this was going on, negotiations were under way between Britain, France and Russia. The Soviets wanted mutual aid -- but they also demanded military bases in Poland and Romania. Britain would not give in to their demands. And of course, while all this is going on, Russia was conducting secret talks with Germany. The result of all this was that on August 23, 1939, Ribbentrop and Molotov signed the NAZI-SOVIET PACT of non-aggression. One section of this Pact -- even more secret than the Nazi-Soviet Pact itself -- called for the partition of Poland between Germany and Russia. The Nazi-Soviet pact served as the green light for the invasion of Poland and on September 1, 1939, German troops marched into Poland. Britain and France demanded that Hitler stop his forces but Hitler ignored them and so Britain and France declared war on Germany. Using the Blitzkrieg or lightening war, Poland succumbed to Germany on September 27, 1939. The task of imposing what came to be known as "the final solution of the Jewish Problem," was outlined at a conference held on January 20, 1942. One result of the WANNSEE PROTOCOL, was that a portion of the responsibility for the extermination of European Jewry was given to HIMMLER'S SS. The SS responded with fanaticism and bureaucratic efficiency. The Jews were identified with Reason, Equality, Tolerance, Freedom and individualism. The Jews had no Kultur. Though perhaps German born, they were not a people of the Volk. The SS enjoyed their work a great deal. They regarded themselves as idealists who were writing the most glorious of chapters in the history of Germany. In Russia, special squads of the SS -- the Einsatzgruppen, trained for genocide -- entered captured towns and cities and rounded up Jewish men, women and children who were herded into groups and then shot en masse. About two million Russian Jews perished as a result. In Poland, Hitler established ghettoes where some 3.5 million Jews were forced to live, sealed off from the rest of the population.

The task of imposing what came to be known as "the final solution of the Jewish Problem," was outlined at a conference held on January 20, 1942. One result of the WANNSEE PROTOCOL, was that a portion of the responsibility for the extermination of European Jewry was given to HIMMLER'S SS. The SS responded with fanaticism and bureaucratic efficiency. The Jews were identified with Reason, Equality, Tolerance, Freedom and individualism. The Jews had no Kultur. Though perhaps German born, they were not a people of the Volk. The SS enjoyed their work a great deal. They regarded themselves as idealists who were writing the most glorious of chapters in the history of Germany. In Russia, special squads of the SS -- the Einsatzgruppen, trained for genocide -- entered captured towns and cities and rounded up Jewish men, women and children who were herded into groups and then shot en masse. About two million Russian Jews perished as a result. In Poland, Hitler established ghettoes where some 3.5 million Jews were forced to live, sealed off from the rest of the population.I estimate that at least 2,500,000 victims were executed and exterminated [at Auschwitz] by gassing and burning, and at least another half million succumbed to starvation and disease, making a total dead of about 3,000,000. This figure represents about 70% or 80% of all persons sent to Auschwitz as prisoners, the remainder having been selected and used for slave labor in the concentration camp industries. . . .The final solution of the Jewish Question meant the complete extermination of all Jews in Europe. I was ordered to establish extermination facilities at Auschwitz in June 1941. It took from three to fifteen minutes to kill people in the death chamber, depending upon climatic conditions. We knew when the people were dead because their screaming stopped. We usually waited about one-half hour before we opened the doors and removed the bodies. After the bodies were removed our special commandos took off the rings and extracted gold from the teeth of corpses. . . .The way we selected our victims was as follows. . . . Those who were fit to work were sent into the camp. Others were sent immediately to the extermination plants. Children of tender years were invariably exterminated since by reason of their youth they were unable to work. . . . We endeavored to fool the victims into thinking that they were to go through a delousing process. Of course, frequently they realized our true intentions, and we sometimes had riots and difficulties due to that fact. Very frequently women would hide their children under clothes, but of course when we found them we would send the children in to be exterminated.

Although the European resistance was proof that some people refused to accept Hitler and the Nazis, their efforts did not bring an end to the war. Japan's imperialist endeavors from the early 1930s on and including the attack on PEARL HARBOR on December 7, 1941, forced the United States to end its isolationist position and enter the war. Meanwhile, Hitler had made the same blunder as had Napoleon, by attacking Russia in winter. In February 1943, almost 300,000 soldiers died in the battle of Stalingrad and another 130,000 were taken prisoner. And in the fall of 1943, Allied forces liberated Italy. Mussolini was dismissed, and eventually shot and hung by his ankles in April 1945. Finally, on June 6, 1944 -- D-Day -- the Allies landed 2 million men on to the beach head at Normandy. By August, the Allies liberated Paris and then Brussels and Antwerp. Meanwhile, the Allies were conducting massive bombing raids on German industrial cities. The Russians drove across the Baltic states, Poland and Hungary and by February 1945, they were 100 miles from Berlin. By April, American, British and Russian troops were moving toward Berlin from all sides. On April 30, 1945, Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide and one week later, May 7, a demoralized and near destroyed Germany surrendered unconditionally. Finally, on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima -- 78,000 perished within fifteen minutes of the blast. Three days later, another bomb fell on Nagasaki and on August 14, Japan surrendered.

Although the European resistance was proof that some people refused to accept Hitler and the Nazis, their efforts did not bring an end to the war. Japan's imperialist endeavors from the early 1930s on and including the attack on PEARL HARBOR on December 7, 1941, forced the United States to end its isolationist position and enter the war. Meanwhile, Hitler had made the same blunder as had Napoleon, by attacking Russia in winter. In February 1943, almost 300,000 soldiers died in the battle of Stalingrad and another 130,000 were taken prisoner. And in the fall of 1943, Allied forces liberated Italy. Mussolini was dismissed, and eventually shot and hung by his ankles in April 1945. Finally, on June 6, 1944 -- D-Day -- the Allies landed 2 million men on to the beach head at Normandy. By August, the Allies liberated Paris and then Brussels and Antwerp. Meanwhile, the Allies were conducting massive bombing raids on German industrial cities. The Russians drove across the Baltic states, Poland and Hungary and by February 1945, they were 100 miles from Berlin. By April, American, British and Russian troops were moving toward Berlin from all sides. On April 30, 1945, Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide and one week later, May 7, a demoralized and near destroyed Germany surrendered unconditionally. Finally, on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima -- 78,000 perished within fifteen minutes of the blast. Three days later, another bomb fell on Nagasaki and on August 14, Japan surrendered.

Soviet troops at the Brandenburg Gate

the Fuehrer inspects boy-soldiers

defending Berlin April 20, 1945

Hammer & Sickle atop the Reichstag

at Russian headquarters, Berlin May 9, 1945

II

III

What secret did he take to the grave?

“Semi-blind, his memory gone, he languished for 46 years in prison, and spent over half of that time in solitary confinement. At first, he was detained in cells with blackened windows, sentinels flashing torches on his face all night at half-hour intervals, and later in conditions only marginally more humane.“Occasionally, mankind remembered that he was there: at a time when political prisoners were being released as a token of humanity, the world knew that he was there in Spandau, and timid souls felt somehow the safer for it. In 1987 the news emerged that somebody had recently stolen the prisoner’s 1940s flying helmet, goggles, and fur-lined boots, and fevered minds imagined that these, his hallowed relics of 1941, might be used in some way to power a Nazi revival.“The prisoner himself had long forgotten what those relics had ever meant to him. The dark-red brick of Spandau prison in West Berlin was crumbling and decaying around him, and the windows were cracked or falling out of mouldering frames. He was the only prisoner left – alone, outliving all his fellows, his brain perhaps a last uncertain repository of names and promises and places, grim secrets that the victorious Four Powers might have expected him to take to the grave long before.“The prisoner was Rudolf Hess, the last of the “war criminals.” In May 1941 he had flown single-handedly to Scotland on a reckless parachute mission to end the bloodshed and bombing. Put on trial by the victors, he had been condemned to imprisonment in perpetuity for “Crimes against the Peace.” The Four Powers had expected him to die and thus seal off the wells of speculation about him, but this stubborn old man with the haunting eyes had by his very longevity thwarted them.“Few questions remained about the other Nazis. Hitler’s jaw bone was preserved in a Soviet glass jar; Ley’s brain was in Massachusetts; Bormann’s skeleton was found beneath the Berlin cobblestones; Mengele’s mortal remains were dis- and reinterred; Speer had joined the Greatest Architect. Dead, too, were Hess’s judges and prosecutors.Hess himself was the last living Nazi giant, the last enigma, unable to communicate with the outside world, forbidden to talk with his son about political events, his diary taken away from him each day to be destroyed, his letters censored and scissored to excise illicit content. The macabre Four Powers statute – ignored, in the event – ordained that upon his death his body was to be reduced to ashes in the crematorium at Dachau concentration camp. The bulldozers were already standing by to wreck Spandau jail within hours of his decease, so that no place of Nazi pilgrimage remained.“For forty years this Berlin charade was the sole remaining joint activity of the wartime Allied powers, a wordless political ballet performed by the Western democracies and high-stepping Red Army guards. Every thirty days the guard was rotated. Each time that the British or the American or the French came to hold the key, they could in theory have turned it and set this old man free. But they did not, because the ghosts of Churchill, Stalin, and Roosevelt were themselves the jailers. In the name of a Four Power agreement that had long since been dishonored, these ghosts kept Hess behind bars; and so Hitler’s deputy lived on in Spandau, mocking history and making a mockery of justice itself.“Despite everything, he became a martyr to a cause. Mankind dared not turn the key to set him free, and mankind did not know why.”Hess Family Grave - Recently Vandalized

I speculate, as many do, that Hess might well have meant to offer to factions friendly to the Third Reich within the British government a roadmap to the stars.

“Hess planned to meet the Duke of Hamilton and Brandon. He believed Hamilton to be an opponent of Winston Churchill, whom he held responsible for the outbreak of the war. His proposal of peace included returning all the western European countries conquered by Germany to their own national governments, but German police would remain in position. Germany would also pay back the cost of rebuilding these countries. In return, Britain would have to support the war against Soviet Russia. (…)“Churchill turned down the proposal for peace and held Hess as a prisoner of war in the Maryhill army barracks. Later Hess was transferred to Mytchett Place near Aldershot. The house was fitted out with microphones and sound recording equipment. Frank Foley and two other MI6 officers were given the job of debriefing Hess —”Jonathan”, as he was now known. Churchill’s instructions were that Hess should be strictly isolated and that every effort should be taken to get any information out of him that might be useful.“Controversy surrounds the case of whether Hitler knew of Hess’ plans to make peace with Britain. It is known that Hess had been getting flying lessons in a personalized Messerschmitt aircraft in the early stages of this preparation. He was accompanied by Hitler’s personal pilot, Hans Baur.Lured into a trap?“There is circumstantial evidence which suggests that Hess was lured to Scotland by the British secret service. Violet Roberts, whose nephew, Walter Roberts was a close relative of the Duke of Hamilton and was working in the political intelligence and propaganda branch of the Secret Intelligence Service (SO1/PWE), was friends with Hess’s mentor Karl Haushofer and wrote a letter to Haushofer, which Hess took great interest in prior to his flight.“According to data published in a book about Wilhelm Canaris, the head of German intelligence, a number of contacts between England and Germany were kept during the war. It cannot be known, however, whether these were direct contacts on specific affairs or an intentional confusion created between secret services for the purpose of deception. (…)“Certain documents Hess brought with him to Britain were to be sealed until 2017 but when the seal was broken in 1991-92 they were missing. Edvard Bene_, head of the Czechoslovak Government in Exile and his intelligence chief Franti_ek Moravec, who worked with SO1/PWE, speculated that British Intelligence used Haushofer’s reply to Violet Roberts as a means to trap Hess.“The fact that the files concerning Hess will be kept closed to the public until 2016 does allow the debate to continue, since without these files the existing theories cannot be fully verified.

“I had the privilege of working for many years of my life under the greatest son my nation has brought forth in its thousand-year history. Even if I could, I would not wish to expunge this time from my life. I am happy to know that I have done my duty toward my people, my duty as a German, as a National Socialist, as a loyal follower of my Führer. I regret nothing. No matter what people may do, one day I shall stand before the judgment seat of God Eternal. I will answer to Him, and I know that He will absolve me.”

“Keeping one man in Spandau cost the West German government about 850,000 marks a year. In addition, each of the four Allied powers had to provide an officer and 37 soldiers during their respective shifts, as well as a director and team of wardens throughout the entire year. The permanent maintenance staff of 22 included cooks, waitresses and cleaners.“In the final years of his life, Hess was a weak and frail old man, blind in one eye, who walked stooped forward with a cane. He lived in virtually total isolation according to a strictly regulated daily routine. Regulations stipulated that prison officials could not ever call Hess by name. He was addressed only as “Prisoner No. 7.”

“Every year after Hess’s death, nationalists from Germany and the rest of Europe gathered in Wunsiedel for a memorial march. Similar demonstrations took place around the anniversary of Hess’s death. These gatherings were banned from 1991 to 2000 and nationalists tried to assemble in other cities and countries (such as the Netherlands and Denmark). Demonstrations in Wunsiedel were again legalised in 2001. Over 5,000 nationalists marched in 2003, with around 7,000 in 2004, marking some of the biggest national demonstrations in Germany since 1945. After stricter German legislation regarding demonstrations by nationalists was enacted in March 2005 the demonstrations were banned again.Roosevelt Telegram to Churchill

German Occupation of Europe Timeline What the Allies knew Jews of the Channel Islands - The Polish Fortnightly Review

Poland

Austria Belgium Bulgaria Denmark France Germany Greece Hungary Italy Luxembourg The Netherlands Norway Romania Slovakia Soviet Union

|

(Editor's note, the date in this caption was in error, these rocket launchers were not deployed until later in the war.) Soviet rocket launchers fire as German forces attack the USSR on June 22, 1941. (AFP/Getty Images) #

An Sd.Kfz-250 half-track in front of German tank units, as they prepare for an attack, on July 21, 1941, somewhere along the Russian warfront, during the German invasion of the Soviet Union. (AP Photo) #

A German half-track driver inside an armored vehicle in Russia in August of 1941. (Deutsches Bundesarchiv/German Federal Archive) #

German infantrymen watch enemy movements from their trenches shortly before an advance inside Soviet territory, on July 10, 1941. (AP Photo) #

German Stuka dive-bombers, in flight heading towards their target over coastal territory between Dniepr and Crimea, towards the Gate of the Crimea on November 6, 1941. (AP Photo) #

German soldiers cross a river, identified as the Don river, in a stormboat, sometime in 1941, during the German invasion of the Caucasus region in the Soviet Union. (AP Photo) #

German soldiers move a horse-drawn vehicle over a corduroy road while crossing a wetland area, in October 1941, near Salla on Kola Peninsula, a Soviet-occupied region in northeast Finland. (AP Photo) #

With a burning bridge across the Dnieper river in the background, a German sentry keeps watch in the recently-captured city of Kiev, in 1941. (Deutsches Bundesarchiv/German Federal Archive) #

Machine gunners of the far eastern Red Army in the USSR, during the German invasion of 1941. (LOC) #